The Ontario Conference of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ faced the “Spanish” Flu with impatience to be back at public worship and prayed it would end soon. Published response in other Conferences was fairly similar. Did they have other concerns related to the pandemic?

The pandemic was a problem. In the Wakarusa and South West area of the Indiana and Ohio Conference: “the Q[uarterly] M[eetings]…well attended…notwithstanding some were still fearful of the ‘flu’.” At Pleasant Hill– “Some officials were not able to be present on account of sickness at home…” (A B Yoder). From the Michigan Conference, Benjamin U Bowman, P E, reported that at Elkton, MI—Beulah, “There is considerable of the ‘flu’ in these parts and so many were afraid to attend service…some people came home sick…canceled services.” Bowman summarized the problem: “We have been greatly hindered the last two months in holding our Q Ms. Trust that the terrible epidemic that is spreading so rapidly will soon be over.”1 Other Presiding elders and pastors said pretty much the same (eg R M Dodd, W H Moore, W W Culp).

The Pacific Conference faced a different public health timing, and the Presiding Elder Barbezat found he could hold meetings in Oregon but not in Washington State, where William R Grout and family, the pastor at Mt View, were all sick from the flu. But even in Culver, OR, meetings were shut down while he was there.2 Earlier, John G Grout (Yakima, WA) had complained about restrictions in “what a godless man-made age this is getting to be,” in which “people would rather trust in six thicknesses of cheesecloth and some blood-poisoning serum,” than God. You can tell where he would stand with respect to vaccinations today!3 In Nebraska Conference, Timothy and Lulu Overholt at Bloomington, Nebraska, mentioned no services were allowed on their new field yet.4

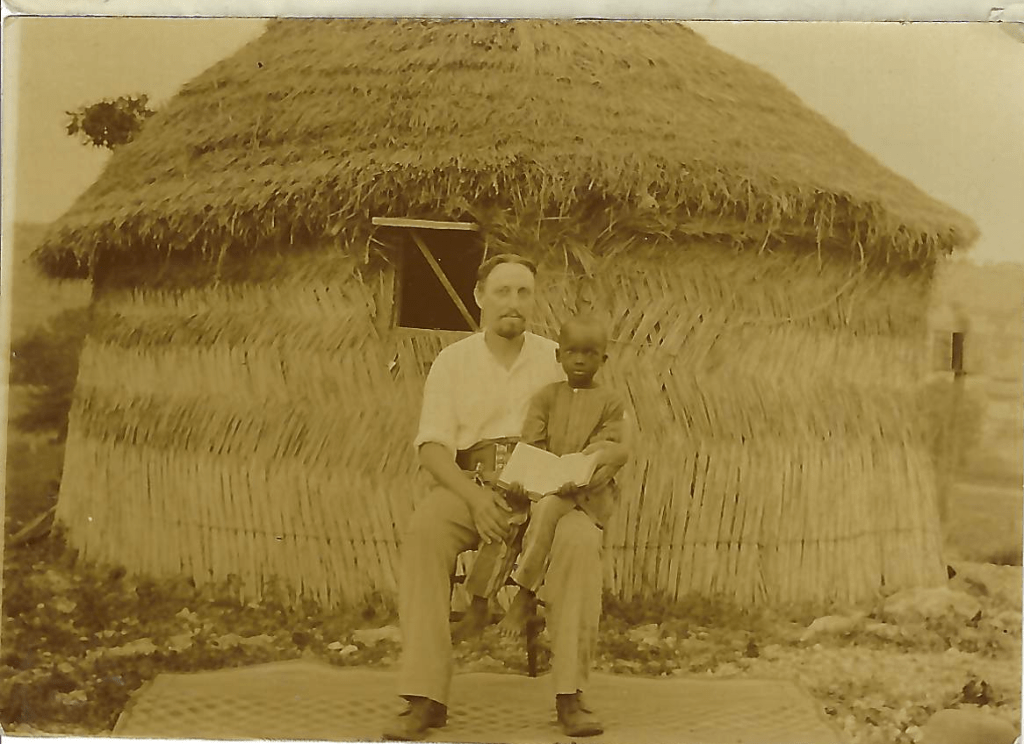

Credit: Huffman, History of the MBiC Church (1920) opposite p 212.

In fact, every Conference of the MBiC reported some problem with the flu, mostly cancellation of meetings due to public bans for some weeks; city mission workers in the MBiC Omaha missions switched to open air meeting in the streets, until, that, too was banned.5 I noted, however, the writers acknowledging peoples’ fear of getting sick in meetings. MBiC leaders seem to discount their fears. The US government kept telling people not to panic but censorship reinforced a disconnect between what people heard and what they read, a perfect condition for panic. But pastors dealt with sickness in themselves and their people all the time from dozens of ailments. In the writers’ view, recoveries from the flu were providential, but the dead were buried in silence.6 Funerals had to be held in homes instead of church buildings. It was an inconvenience.7

The Pandemic deeply affected many countries. It may have affected wars and economies for decades, as John Barry thinks, in his book, The Great Influenza.1 It also changed the religious landscape. In Nigeria, where it is estimated one to two million died, members of the Anglican churches were so distressed by the ineffective spiritual response of their mission-founded (Church Missionary Society) church they separated when ordinary members had visions of another way. Seeking spiritual power for healing and to stop the deaths, several groups became “praying” (Aladura) churches that relied on prayer alone, rejecting Western medicine. Several of those denominations continue today with millions of members each, and they still reject Western medicines.8

https://churchtimesnigeria.net/revival-nigeria-tacn-cleric/

In South Africa new religious groups started when people found western—colonial— medicine failed to heal or stop the spread the disease.9

In India, probably 20 million people died.10

Although Sam Goudie had hoped the flu was over in Ontario at the end of November, his brother Henry was experiencing its continuing effect in the Canada Northwest Conference at the beginning of December: “On account of the present sickness it has been decided to postpone our conventions and conference until after the 7th of January.”11

Lessons. At the 100th anniversary of the “Spanish” flu, the Canadian Centre for Christian Charities reviewed the history and responses of Canadian churches to the pandemic. The writer, John Pellowe, quoted an American preacher’s “lessons learned,” immediately after the worst was over. Rev Grimke concentrated on the lessons, that worshiping together was a gift and that temporary closures for the health of society were justified, (if we love our neighbour, I might add).12 The Gospel Banner printed two responses of an MBiC Ontario preacher, Alfred George Warder, from a Bible Christian/ English Methodist Bruce Peninsula family. (In 1930, Warder drowned trying to rescue a woman at Port Burwell beach on Lake Erie, a lamentable loss.) Warder, the pastor at Collingwood in 1918, with his wife, Michigan-born Mary Maude Detwiler, announced that their church persisted in praise. “Praise…while the noisome pestilence ravaged our land—yea the world.”13 Then Warder found seven lessons from the plague, mostly to do with judgement and God’s offer of salvation, you’ll notice, and little about compassion:

1. God is fulfilling his word

2. Sign of last days

3. [M]ercy is still great

4. “While we don’t take the stand that no good people had the ‘flu’, nor that no bad ones escaped, yet by it God spoke to many who wouldn’t hearken to His Word, nor hear his voice through the great world war.”

5. “That it came suddenly, and swiftly and men couldn’t flee from it…nor the judgement of God. Only by…Jesus.”

6. ‘[T]hat money, wealth, health, friends, race, rank or position is no safeguard—rich and poor share alike…”

7. “That men remember God in the day of adversity, but forget…”14

Warder’s lessons also have nothing to do with opposing government for curtailing Christians’ “freedom” by closing church services for the public good, or for mandating masks. In 2020-2022 North American right-wing political churches were riveted by conspiracy theories, reflecting suspicion of authorities, medical, government and of course rapacious pharmaceuticals. Many evangelical people distrust scientific studies, not understanding how scientists (including medical doctors) have reached where they are today and assume the worst. Warder took the epidemic as a sign of the last days (he was right, any tribulation always is) but he did not pronounce doom on the government or health officials. Medical people will be the first to say, as they did during COVID-19, that their instructions on facing a new threat were provisional, based on the best analogies they had. And they are not saints.

In fact in 1918 nobody knew how to cure influenza. Nobody (Barry, p 579). Vaccines were produced but targeted the wrong cause, so were useless. The attempt to find a cure was not evil, then or now. They suspected it was caused by a small agent that could pass through the best filters available (the masks used were next to useless). The best they could do to slow the spread was, social distance, isolate and give people fresh air. Health officials changed their advice (or individual doctors offered conflicting advice) several times, not because they were manipulating people to prepare for the antichrist, but because that is how science works. Follow the evidence as best you can, and tell the truth.

As it was, in 1918-1920, many churches of Ontario and volunteer societies, many of them Christian, did everything they could to assist people and families harmed by the influenza. I haven’t seen evidence the mainly rural MBiC did. (But so much is unrecorded, as on the Bruce Peninsula: see Part 1). Some Canadian churches opened their buildings as depots for supplies or even temporary hospital wards when the regular institutions were overwhelmed.15 During World War 1, which was just finishing (on November 11), people had become used to government-mandated rationing, and volunteering to support the combatants. Nearly every woman produced items for the Red Cross in the US and Canada, peace church or not.

The Mennonite Brethren in Christ was a peace church, and joined with other Anabaptist churches and Quakers to gather and send relief materials through the Red Cross or (in Ontario) money through the Mennonite Non-Resistant Relief Organization for refugee groups affected by the war.16 In Canada and in the United States, war measures law ruthlessly made many criticisms of the war unpatriotic and traitorous, even though military strategy and pride probably set up the conditions for a new mutation of the influenza virus to flourish. Government agencies did lie and cover up the extent of deaths, all in the name of keeping up “morale.” Before reading John Barry’s book, I did not know either that many anti-German and anti-Mennonite actions in American communities must have been state-sponsored, not merely popular prejudice as I supposed.17 The climate of fear produced by the new laws must have shaped the mild language of the MBiC in its leaders’ statements as well.

Courtesy: Hunking Family Collection, MCHT

I have seen only one MBiC story of resistance to the plague in prayer, neighbourhood relief, or miraculous healings. Ontario’s Charlie Homuth and his wife (Sarah Jane Davis) had been MBiC missionaries to Nigeria, but in 1918, Charlie having returned from Nigeria, they were ministering in Winnipeg, Manitoba, at the Home of the Friendless. This was an interdenominational relief organization run by “Sister Crouch,” a Methodist lady from the USA.18 Homuth had an eventful life that merits a post someday. Writing from West Kildonan, Winnipeg, Homuth reported an answer to prayer for coal for the missions’ boys’ home. “The past month has been a time of special need on account of so much sickness, which naturally incurs added expense…We have not been able to have any services for some weeks on account of this epidemic getting hold of the children which is so prevalent over the land. However the Lord has been undertaking and over-ruling the sickness to the salvation of some and arousing many others… Our beloved superintendent, Sister Crouch, has ministered night and day to the suffering ones. Many were touched in answer to prayer. Different ones were wonderfully healed.”19

Maybe there were some other healings, but the dominant desire in the Church was to get back to “normal” and the dominant feeling was relief once the pandemic had (they hoped) passed. They were not prepared for the unexpected pandemic. We don’t have any such excuse.

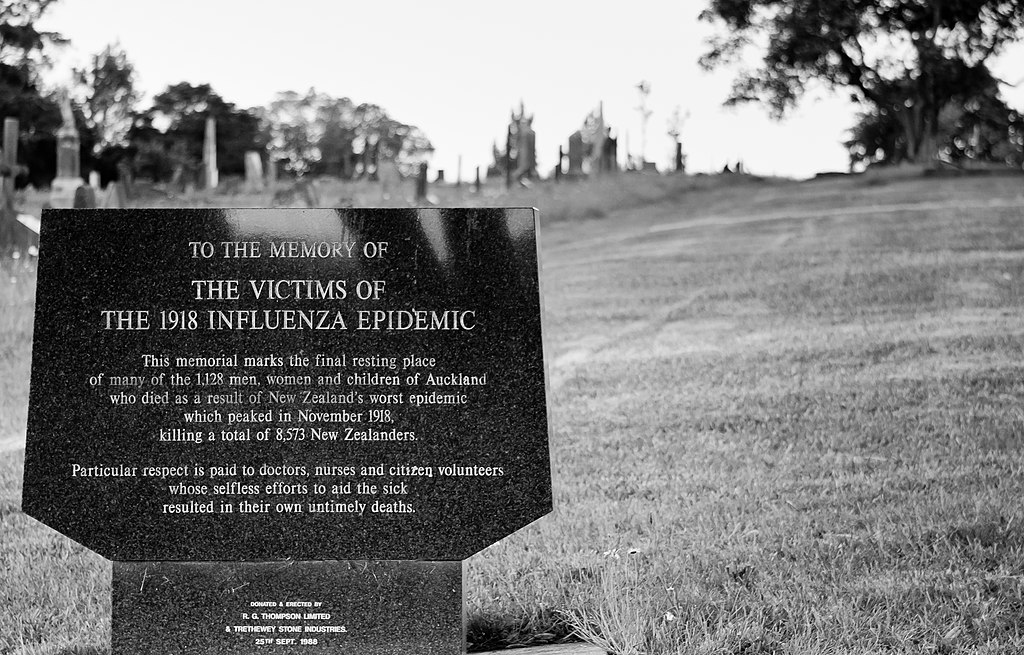

Banner: One of the handful of public memorials around the world to acknowledge the losses to the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic. This one is in New Zealand. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

1“Reports—PE,” Gospel Banner (December 5 1918) p 12.

2Alfred W Barbezat, “Reports—PE—Pacific Conference,” Gospel Banner (November 28 1918) p 12.

3John G Grout, “Reports—Pastors,” Gospel Banner (November 21, 1918).

4Timothy and Lulu Overholt, “Reports—Pastors,” Gospel Banner (November 7 1918) p 13.

5Ellen Flesher and Edna V Jacobson, “Reports—Missions—South Omaha,” Gospel Banner (October 24 1918) p 13, and November 14 1918) p 13.

6All Conferences except Pennsylvania, that is. They published their own Eastern Gospel Banner 1917-1924; Everek R Storms, History of the United Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1958) p 73.

7“Deaths,” Gospel Banner (October 24 1918) p14.

8 Olushola Ojo, Tahir Kamran and Huma Pervaiz, (2025) “Socio-Economic Impacts of 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic in Lagos” https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=140874

9Alex de Waal, New Pandemics, Old Politics: Two Hundred Years of War on Disease and its Alternatives (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2021) p 95-97.

10John M Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, rev ed (Penguin/ Random House, 2018), p 588-589.

11Henry Goudie, “Notice,” Gospel Banner (December 5 1918) p 14. The same issue still carried his announcement for the annual conference and revival meetings for Dec 5-7!!

12 John Pellowe (2021),

13Alfred G Warder, “Reports—Pastors—Collingwood, ON,” Gospel Banner (November 14 1918) p 12.

14Alfred G Warder, “What I Learned from the Flu Epidemic,” Gospel Banner (December 19 1918) p 5.

15Karen Black (2020), https://www.tvo.org/article/how-ontarians-came-together-to-fight-the-spanish-flu

16James Clare Fuller, Hidden in Plain Sight: Sam Goudie and the Ontario Mennonite Brethren in Christ (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock/ Hamilton, ON: McMaster Divinity College Press, 2024) p 230-232.

17Woodrow Wilson set the tone of ruthlessness; Barry, p 187-257. Recognize the book is fairly America-centred. Canada doesn’t exist.

18I referred to this institution in the second of the two blogs EMCC History “Whatever Happened to the Manitoba Mission?” Part 2, June 1 2024.

19Charles Tobias Homuth, “West Kildonan, Winnipeg, Canada,” Gospel Banner (December 5 1918) p 14-15.

- John M Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History rev ed (Random House/ Penguin, 2018), p 614-622. ↩︎

Leave a reply to samjaysteiner Cancel reply