There was a time when members of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ and then United Missionary Church just never entered a movie theatre, as several readers in places such as Stratford and Stouffville tell me.

The door opens a crack. The disposition against movies was widespread in the UM Church, but the times were changing. Back in 1947, the Toronto West MBiC church that became Banfield UMC (now Wellspring Worship Centre), took a request to the MBiC Ontario Conference meeting in Stouffville, ON:

“Whereas a number of our Sister Churches [referring to other denominations] are using religious films with the sound projector, and

Whereas questions are arising in the minds of many of our people regarding the advisability of such moving pictures in our churches, we request Annual Conference to make an authoritative statement as to whether or not such may be used.”1

By Conference action, Standing Rule #17 stated, after affirming that preaching was the top priority to proclaim the gospel,

“Whereas we are aware of the undesirability of certain types of religious films which are commercially produced by unsanctified persons, therefore, We strongly urge our local fields to be discriminating in the types of religious pictures used and place given to them, and that in as much as possible church auditoriums be not used for such purposes.”2 This standing rule remained in the Journals annually until 1968.

Breaking the habit. My classmates at Emmanuel Bible College (1977-1981), claimed to have persuaded one of our professors to enter a movie theatre for the first time. We drew him with the prospect of seeing Ralph Bakshi’s semi-animated 1978 film, The Lord of the Rings. Another fellow minister, I understand by hearsay, entered a cinema for the first time to see the 2006 film, The Nativity Story. (Don’t quote me on that one.) Shanny Luft began his PhD dissertation with an anecdote of the editor of The Fundamentalist explaining to his son in 1984, why their family did not go to movies.3 What’s behind the reluctance of the early and not-so-long ago EMCC to watch commercial films in a cinema? And what happened to erode the caution?

The 1947 Standing Rule #17 in the Ontario Conference of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ, which that year became the United Missionary Church, did not forbid the use of religious films by the congregations, but urged churches to use discrimination in their use and avoid using the regular worshiping space as the location for showing films.4 They were nervous about sullying the “sanctuary,” I suppose. The Rule did not directly address watching non-religious film, commercial films, “Hollywood” films. Those were assumed to be too ungodly to need direction.

Somewhere I read the argument that “You wouldn’t invite a guest to your house who regularly smoked, swore, lied and slept with people other than their married spouse, would you?” In fact, people could and did watch people doing exactly those things on TV from the 1950s onward in the privacy of their own home. One of the arguments against commercial (“Hollywood”) films had long been the immoral lifestyles of the actors, widely publicized in tabloid magazines. A Christian’s speech in contrast is expected to match their life. It is jarring to hear an actor speak wise or pious words on film when you read or hear that they cheat on their income tax or on their spouse, divorce frequently, gamble, constantly consume luxuries or harmful substances and neglect their children. Not that actors have a monopoly on these behaviours.

Then there are the actors (and movie scripts) whose opinions were racist, sexist, jingoist, or disparaged biblical teaching. Many movies assume or are in favour of “redeeming” violence and war as a way of solving personal or national problems.5 Until 1962, the MBiC/ UMC advocated biblical non-resistance.6

What “religious films” might the 1947 Ontario MBiC/ UMC Rule have had in mind? I mentioned a few theatrical ones in the related blog, such as the The Last Days of Pompeii (1935) or The Great Commandment (1939). Although re-released in 1944 with new framing narrative and edited to remove the most objectionable scenes, Cecil B DeMille’s 1932 The Sign of the Cross, would still have been far too worldly to imagine the MBiC/ UMC showing it. These were all in 35 mm format used in commercial cinemas, needing expensive sound equipment churches could not afford anyway. After the Second World War, the American military sold off surplus training 16 mm film projectors to Christian film producers who used them to make the religious film market possible.7

Credit: YouTube

Something called My Son, My Son 1940 was available, probably referencing David’s grief over Absalom. There was, also, a British “Life of Paul” series of 1938, made for church use. The new Cathedral Films produced 15 minute short films for Sunday Schools in 16 mm on the Life of Christ, starting in 1940, The Good Samaritan, followed by 20-minute films such as A Certain Nobleman and The Child of Bethlehem. Carlos Baptista’s 10 minute The Rapture 1941 was the first of the apocalypse/horror movie genre.8

The Hollywood blockbusters of the 1950s were still in the future: Samson and Delilah 1949, David and Bathsheba 1951, Quo Vadis 1951, The Robe 1953, Demetrius and the Gladiators 1954, The Ten Commandments 1956, and Ben-Hur 1959.

Possibly the first use of film for an evangelistic purpose in the UMC in Ontario would be about 1952 when pastor Alf Rees, a WW II vet of the Royal Canadian Airforce, used The Amazing Story of Sgt Jacob DeShazer. It was produced for the School of Missions, Seattle Pacific College by Great Commission Films. He showed it in a Legion hall in Paisley and many came to see it. (Immanuel EMC history, p 13.)

Soon after the Ontario Conference rule, a new source of Christian film emerged. Billy Graham was the first staff member of Youth for Christ (founded in 1944/45).9 His generation was not afraid of film. YFC produced through Gospel Films (and Ken Anderson’s direction) a number of short films in the 1950s.10 Gospel Films’ efforts were condemned by the widely respected A W Tozer around 1954 in a pamphlet called The Menace of The Religious Movie.11 Nevertheless, the popular YFC youth rallies at a Baptist church in Markham Township used the films. It broke up some of the reluctance in nearby UMC congregations to attend screenings of motion pictures in church buildings.12 Youth for Christ had quite a number of connections with Missionary Churches in Canada and the USA, which Ontario YFC staff member and licensed EMCC minister Frank Braun demonstrated. [“Parallel Streams Irrigating God’s Kingdom: Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada and Youth for Christ,” Emmanuel Bible College class paper, 2001, Box 7201, MCHT]. A photograph in the MCHT collection, of the front of the UMC Petrolia Church building about 1954 clearly shows a poster for the 1953 BGEA film Oiltown, USA.

UMS media. Audio and audio-visuals were being used by the UMC, in the form of Long Play vinyl recordings, and film strips. The United Missionary Society opened a UMS Film Service, and recommended Billy Zeoli’s Gospel Films Inc, with 5 locations to rent from (2 in Canada).13 In 1960, the UMS listed 5 slide shows of their own with reel to reel tape recordings, from 15 to 35 minutes long.14 By 1962, they offered 9 filmstrips, a tape recording of missionary Annie Yeo’s account of her escape from a torpedoed ship in the Second World War, and a message from Willis Hunking on 12-inch vinyl.15 The Women’s Missionary Society invited Harry Percy of the Sudan Interior Mission to show Rip Tide, a film “depicting the many phases of life and religions in Africa…”16 The UMS produced films of its own, such as the 1960 Souls in Despair, a 27 minute 16 mm film on the UMS in Brazil, filmed by R S (“Dick”) Reilly, the UMS foreign secretary since 1954, and Quinton Everest, chair of the UMS board. Produced by King’s Productions, it was narrated by Everest. The film promoted the new (1955) Brazil field of the UMS. In 1966, the UMS announced Task Unfinished, a sound-Color Motion picture, 25 minutes about Nigeria.17 Unfortunately, most of these media seem to be lost from Missionary Church archives. Later there were many Missionary Church media productions which I will look at in the third blog of this series.

Something that did not get lost was a film from the late 1970s called The Salka File, a dramatized account of the mid-1970s awakening among the Kambarri people of Nigeria. The awakening led to thousands of converts and numerous congregations centred on the town of Salka in middle belt Nigeria after 50 years of minimal response. It exists on 16 mm film and a VHS version in the Missionary Church Historical Trust.

By the 1960s, films, not named, were being used in the camp meetings, or at least the youth camp, Pinewagami, at Stayner.18 The Montreal World’s Fair, “Expo 67,” reluctantly allowed an evangelical Christian pavilion that used Moody Science films in evangelistic events.19 Many congregations across Canada supported Sermons from Science, including my family’s new home congregation in North Bay, some to attend, some to serve as counselors. We prayed for its efforts. So by 1969, in the merged Missionary Church in Ontario at least, advice about the use of motion pictures was overcome by events.

In the 1970s, the District Superintendent’s monthly newsletter, The Dispatch/ Canada East Dispatch, carried reports from pastors about events in their congregations. By then, some pastors were regularly using films in their churches, mostly in the evening services and in youth meetings. In a four-year sampling (1973-1976), I noted many recently-produced films. Pastors reported on Gospel Films’ Journey to the Sky (1969, life of India’s Sadhu Sundar Singh), Moody Science films (The Ultimate Adventure, The City of the Bees), Billy Graham/ WorldWide Pictures (Time to Run 1973, For Pete’s Sake 1974, The Gospel Road 1973-very popular, featuring Johnny Cash). One church used Gateway Films’ The Cross and the Switchblade 1970, the first evangelical movie to make a profit theatrically.

There were some older narrative films by independents, Centreville Awakening 1958, My Son, My Son 1940, Not With a Sword-a life of David, and the newer Christian apocalypse/horror films: A Thief in the Night 1972, (A Distant Thunder, the sequel, showed up in 1977) The Rapture, Gospel Films’ The Enemy 1974, and popular with some, The Burning Hell 1974. These were shown even though some followed a pretribulation rapture dispensational eschatology the Missionary Church did not officially teach. At some point probably in the late 1960’s or early 1970s our congregation in North Bay showed the Tony Fontane biopic, The Tony Fontane Story.20 I had never heard of him, but I recognized the genre—conversion from a worldly life of nightclub entertaining after amazing recovery from a coma resulting from a car crash, leading to years of singing as a Christian in church meetings.

Some films are so obscure the internet does not easily identify them, such as Africa: Dry Edge of Disaster used on a World Relief Sunday, probably a documentary. I haven’t been able to identify others: The Occult, The Sounds of Love, Troubled Waters, Beloved Enemy, Isn’t it Good to Know. Some of these may be missionary stories, such as the acclaimed Rolf Forsberg/ Don Richardson film, the half-hour Peace Child 1972.

Credit: Internet fair use image

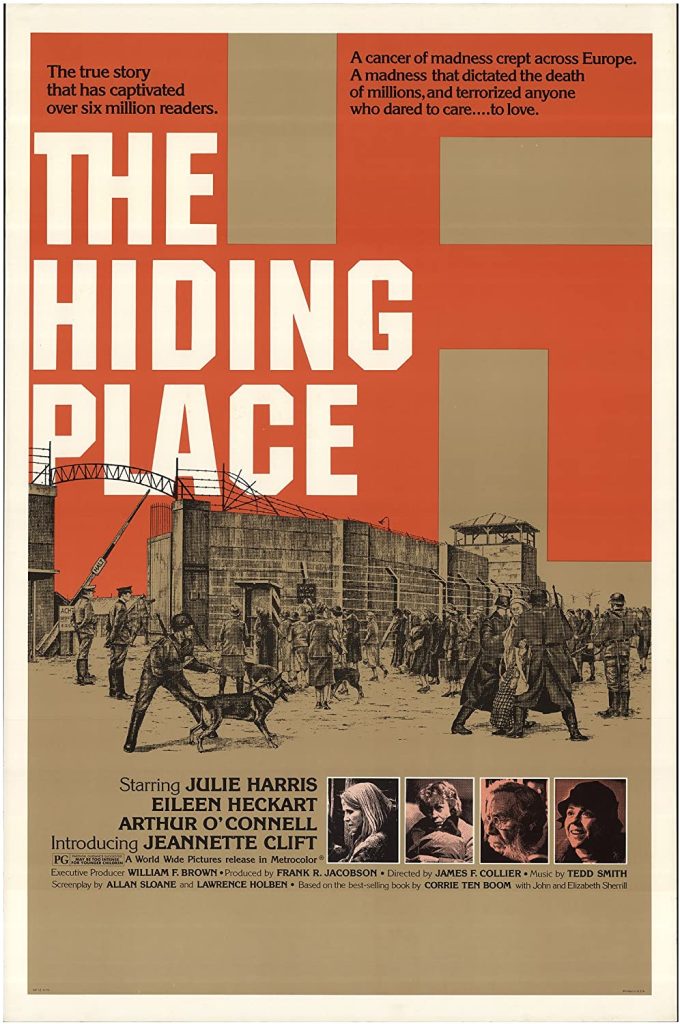

You will notice none of these are Hollywood blockbusters, which were not available for church use anyway until the rise of VHS video cassettes. I suspect Billy Graham’s films were also being used, such as The Wiretapper 1955, The Restless Ones 1965 (first WWP theatrical release), Two a Penny 1967 (set in England), and The Hiding Place 1975. I am pretty sure, though I never saw The Restless Ones, that our church youth group sang a song used in the film fairly soon after its release, and other Billy Graham movie songs later. The video cassette, VHS, by the way, destroyed the evangelical film library system that had developed since the 1950s.21 I will investigate the films that the libraries stocked and those that followed in a later blog.

The Hiding Place, depicting the life of Corrie ten Boom and her family in Holland hiding Jews in their house during World War II deserves a few more comments. A stage play of the same name has recently toured and been filmed (2023) for viewing.22 The BGEA promoted ten Boom although she already had a large teaching, reconciliation and evangelistic ministry of her own after the war. The Graham organization involved churches in showing the film in commercial theatres as evangelistic events. My mother was an usher at the shows in North Bay. She came out saying she could not look at people in uniform the same (all Nazis in the film) after witnessing the story many times.

This use of churches to promote films in commercial theatres was adapted by Inspirational Films for Twentieth Century-Fox/ Warner Brothers’ Chariots of Fire 1981, a British movie, which Thomas Fuller has explored in a recent post on his blog Non-Zero Sum Report, https://thomasyfuller.substack.com/p/how-chariots-of-fire-was-marketed

Banner: Group picture from Ralph Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings. Credit: Nerdist

1Ontario Conference Journal 1947, p 30-31.

2Ontario Conference Journal 1948, p 11.

3Shanny Luft, “The Devil’s Church: Conservative Protestantism and the Movies 1915-1955,” PhD Dissertation, University of North Carolina, 2009, p 1.

4See EMCC History blog “Movies and the EMCC Part 1.”

5Such as Charlton Heston, John Wayne, and a host of others; Kristin Kobes du Mez, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (New York: Liveright Corporation, 2020).

6See EMCC History blogs on Peace and War, of June 29 and July 6 2024.

7Quicke, p 73.

8Timothy Beal, “The Rise and Fall of Evangelical Protestant Apocalyptic Horror: From A Thief in the Night to Left Behind and Beyond,” in Gastón Espinosa, Erik Redling and Jason Stevens, ed, Protestants on Screen (Oxford: OUP, 2023) p 282. Baptista’s film was 10 minutes long in 16 mm.

9James Hefley, God Goes to High School (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1970) p 24-26.

10Hefley, p 61.

11Still existing in shorter and longer versions online at truechurch.com and biblebb.com, respectively.

12Dr Allen Stouffer, personal communication.

13Missionary Banner (November 1960) p 15.

14“UMS Film Service,” Missionary Banner (August 1960) p 9, 15.

15Missionary Banner (April 1962) p 14.

16Missionary Banner (April 1962) p 12.

17Missionary Banner (July1966) p 16. This had been in the works since about 1962, the script was to have been by Eileen Lageer; “UMS Board Meets,” Missionary Banner (April 1962) p 8-9.

18“Film rental,” in the financial reports; Ontario Conference Journal 1964, p 50, also in 1967, p 51. No titles were recorded in the minutes.

19Gary Miedema, For Canada’s Sake: Public Religion, Centennial Celebrations, and the Re-making of Canada in the 1960s (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005) p 150-154.

201962. Fontane’s parents had led a Christian mission in Iowa. He rejected their faith, so in his 1957 conversion he knew where he was going.

21Quicke, p 77.

Leave a comment