Why are there no discussions about the problem of “Men in Ministry”?1 Think about that while we turn to the disabilities that hampered and practically shut down the public ministry of women in the early EMCC in Ontario by about 1946. Since 1885, at least 133 women had been approved for preaching, teaching, church planting and pastoral care. This count does not include female missionaries (12 of whom to 1945 had not been City Mission workers), who until an administrative change by the denomination in the later 20th century, were all classed as “clergy” for passport purposes.2 In the 1930s and 40s, the workers in Ontario were declining in numbers while their average age was increasing. Congregations requested men to replace the women in the leadership.

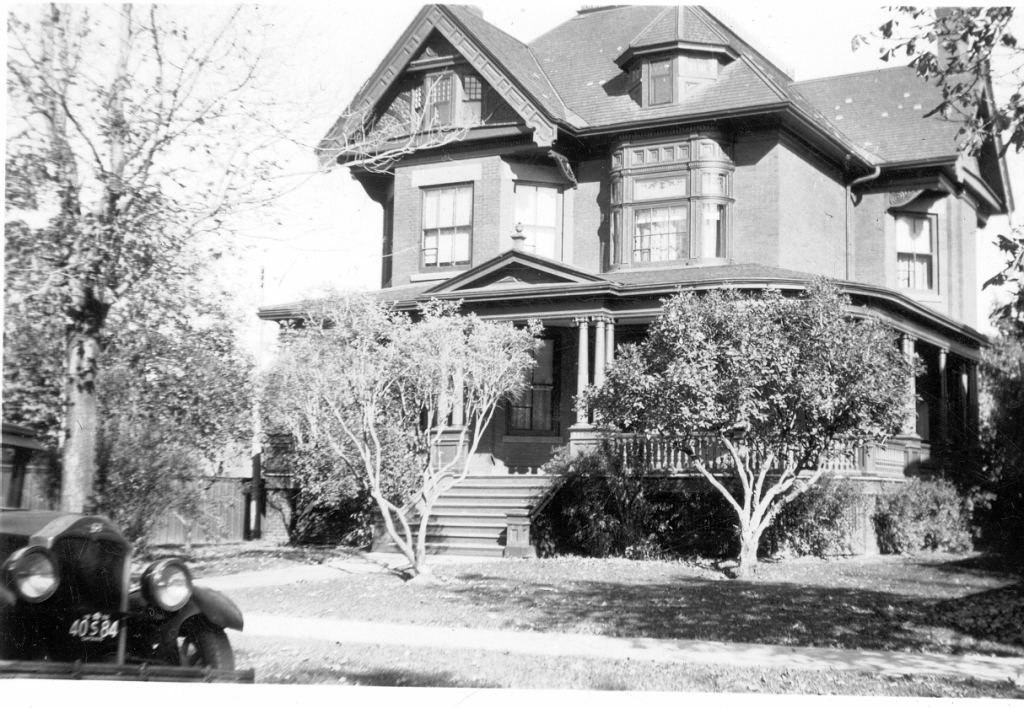

Courtesy: Missionary Church Historical Trust

Rural. Grade 8. The MBiC in Canada, and even well into the United Missionary Church era (1947-1969), was largely a rural denomination, and few members were wealthy.3 The average education of the men up to 1920 can be inferred from the 180 profiles collected in the first history of the binational Church edited by Jasper A Huffman.4 Most of the men reached eight grades of schooling, only 10 attended high school, and several took post-elementary training of a business or trades-related nature. Twenty men reported they took at least one semester of a Bible School course. The church did not have or use seminaries which the majority of denominations did in the latter half of the 19th century. Only one man (Huffman himself) graduated with theology degrees, and two men were medical doctors.5 I do not consider being raised on the farm a disadvantage for a minister, male or female, or only primary school education as a barrier to following a genuine call of God. Some of Jesus’ first disciples were “unschooled” fishermen (Acts 4:13 NIV). It is the attitude of the home and church that encourages or restricts people engaging with God’s world and Word in a public way. By the later 19th century, MBiC women probably had practically the same educational level as the men, with similar advantages and disadvantages.

How the program ended. When the low condition of the women’s ministry was finally acknowledged in 1948, District Superintendent Percy G Lehman, reporting to the annual Ontario Conference, said,

“Trends of the past few years clearly indicate that the field of service for sister workers in the Conference is gradually narrowing. This condition cannot be blamed on any person, but rather is a situation that has come upon us…. It would seem strange that the only Christian work open for young ladies is on the Foreign Mission Field. God has poured out his Pentecostal blessing upon all flesh, upon men and maidens…I feel that this matter should receive our prayerful and sympathetic considerations at this Conference.”6

Courtesy: Missionary Church Historical Trust

The Conference did act by appointing a committee of 8 (6 men, 2 women) who reported later in the proceedings recommending the creation of a Home Mission Board to oversee service open to men and women. This report was adopted and nine members were elected (all men) to begin implementing their plan.7 This well-meaning response unfortunately nearly always discourages young women to consider serving in public roles in an era of male dominance as long as only men lead, and it did not work in this case either. It did not help that Annie Black (1914-1990), who had just completed the regular probationers’ reading course and was being prepared to proceed to dedication, was deferred by the conference, while Paul Storms’ ordination was approved.8 Black requested her name be removed from the Conference roll in 1951 after two years without an appointment. She had served at Wingham and Port Hope, 1944-1949. Black was never moved forward after this. Almost no woman ever applied to serve in Home Missions who wasn’t already serving.

A slowly growing number have been licensed in more modern times since Sandra Tjart received a license in 1979. An application for ordination by Barb Sparks was blocked at a district conference in the 1990s, leading to extensive and inconclusive discussions. The EMCC has recently apologized to her for the treatment she was given. Nevertheless, in 2019, 42 women held EMCC credentials, including 13 ordained women and 7 missionaries.9 In 2024 I heard there were over 60 credentialed women. This year the American Missionary Church had 147 female pastors (half of them Latina) and 21 of those Latina church leaders were what we call “senior pastors.”10

The women of the MBiC city mission program faced low remuneration (so did the men), low esteem by the world because of their nonconforming life styles (so did the men) and an unpopular presentation of a gospel that sought conviction of sin and a high standard of moral life to follow (very much the same as the men). Let me acknowledge here the similar judgement of Charles Gingerich on the difficulties that MBiC women experienced in their ministries, in his MA thesis for Dr Mark Noll at Wheaton College.11 However the women had several disadvantages men did not have, even in the early EMCC.

I group the disadvantages for women under five headings. Here is the first:

#1. Theological double-mindedness. The holiness movement was fairly immune to Reformed and dispensationalist attempts to shut down women’s public ministries.12 The MBiC around 1884 accepted the Methodist view of Acts 2 that NT prophecy13 is basically gospel proclamation: preaching, in other words. Percy Lehman’s appeal to the “Pentecostal blessing” referred to this. Holiness theologians Phoebe Palmer and Catharine Booth defended this view.14

In the Gospel Banner, writers who supported women preachers included Indiana United Mennonite Church elder John Krupp, “Women Speaking in Church,” (Oct 1878); Free Baptist preacher Laura (or Lura) Mains from Michigan, “May Women Pray, Testify or Preach in Public Meetings?” (May 1883); Ontario MBiC elder Moses Weber, “Women Preaching according to the Word of God and our Church Discipline,”(1893);15 and Ontario City Mission Worker Emma Hostetler, “Scripture and Inferential Proof That Woman is Called and Should be Designated to the Work,” (1903).16 So if the Holy Spirit was given to a woman or man with the accompanying gift of (NT) prophecy, then who were we to oppose a woman preaching and all the implications of that? There is more biblical support than that, of course, and some contrary, or apparently so, which Timothy Erdel examined in his review.17 Unfortunately for the women, the question of authority to proclaim is complicated by the question of authority to lead (eldership) and a requirement of wives to submit to husbands and other issues. On a simple level proclamation of the Word of God surely implies leadership in teaching, so the two authorities are intertwined.18 The MBiC never came to a clear theological resolution of that combination of authorities in official teaching.

Perhaps the Free Methodists did. Free Methodist leader B T Roberts argued for ordination of women in, Ordaining Women in 1891, but he did not persuade everyone. Free Methodists approved a limited ordination of women, as distinct from licensing in 1911, and the first FM woman to be so ordained in Canada, Alice Walls, was recognized in 1918.19 I think permission was applied reluctantly in practice. It was not until 1974 that they clarified their position to ordain women.20

I will examine the remaining four disadvantages in EMCC History “How to Kill a Program of Women in Ministry Part 2.”

Banner: On the steps of the Collingwood Rest Home ca 1935. L to R: Margaret Neill, Rose Cober, Annie Srigley, Jennie Little, Elder Peter Cober, Martha Doner, Addie Cober, Grace Stevens. Courtesy: MCHT

1At least one humourous e-mail went around the internet in 1997-98 listing the top ten reasons why men should not be ordained, beginning at the bottom with “10. A man’s place is in the army…” Ask me for forwarding!

2Timothy Paul Erdel, review of Ronald W Pierce and Cynthia Long Westfall, ed, Discovering Biblical Equality 3rd ed (IVP, 2021), in Reflections Vols 24-25 (2022-2023) p 105. The change was a sad day for several women, I have heard.

3The Pennsylvania Conference was fast becoming urban and wealthier after 1900.

4Jasper Abraham Huffman, ed, History of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church (New Carlisle, OH: Bethel Publishing, 1920) p 222-276.

5The doctors were Isaac Erb in Canada, and possibly J G Shireman (3 yrs medical studies) in the USA. Dr C Nysewander, MD from Ohio, was an editor, hymnbook compiler and a prominent leader, though not ordained.

6Percy G Lehman, “Report of the District Superintendent,” Ontario Conference Journal (1948) p 24.

7Ontario Conference Journal (1948) p 33, 42, 50.

8Ontario Conference Journal (1948) p 47.

9Personal communication from Sandra Tjart, August 8 2021. Tjart was ordained in 2012.

10Personal communication from Dr Dennis Engbrecht, July 13 2024.

11Charles S Gingerich, “An Experiment in Denominationalism: A History of the Missionary Church of Canada, Ontario Conference, 1849-1918,” MA Wheaton College, 1994, p 63-67.

12Margaret Lamberts Bendroth, Fundamentalism and Gender, 1875 to the Present (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993) p 44 and 124.

13 William Arthur, The Tongue of Fire: or, The True Power of Christianity (London: Charles H Kelly, 1896 [reprint of 1856]) p 59-65; John C English, “‘Dear Sister’: John Wesley and the Women of Early Methodism,” Methodist History 33:1 (October 1994) 26-33.

14 Ruth Tucker and Walter Liefeld, Daughters of the Church (Grand Rapids, MI: Academie Books, 1987); Phoebe Palmer, The Promise of the Father: A Neglected Specialty in the Last Days (1859); Catharine Booth, Female Ministry: or, Woman’s Right to Preach the Gospel (original edition 1859).

15 Gospel Banner (March 7 1893) p 9.

16 Gospel Banner (November 7 1903) p 4-5. Reprinted in Reflections Vol 24-24 (2022-2023) p 18-20.

17Erdel, p 104-117.

18Walter L Liefeld, “Women And The Nature Of Ministry,”Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 30:1 (Mar 1987). Nicholas Miller, “History of Women’s Ordination in America,” has a helpful analysis of the trends; www.academia.edu/5261660/History_of_Womens_Ordination_in_America?email_work_card=view_paper Miller distinguishes those churches accepting women as teachers, preachers and deaconesses—“prophetic” roles—from those which barred women from any but minimal teaching roles, and certainly not as administrators and leaders—“priestly” roles. Examples of the first would include the MBiC and many Pentecostals.

19 John W Sigsworth, The Battle was the Lord’s: A History of the Free Methodist Church in Canada (Oshawa, ON: Sage Publishers, 1960) p 44.

20 https://fmcic.ca/women-in-ministry-fmcna-fmcic/#:~:text=Ordination%20was%20finally%20granted%20to,ordination%20to%20Elder%20would%20follow. I commented on ordination itself in an earlier blog.

Leave a reply to apstouf Cancel reply