While researching for the profiles of NMC preachers I wrote for GAMEO,1 I gradually drew a picture of their unique community. They were Ontario Mennonites, definitely, and they added other features for a made-in-Canada mix. Frequently, Anabaptists who liked the piety of the Methodist revivals simply switched to one of the Methodist denominations available. The new Mennonites, as the NMC and others were informally called even into the 20th century, repackaged Methodist revivalism their own way.

Distinctive mix. 1. Although they adopted some elements of the Methodist revival practices (seeking a definite experience of salvation, the search for assurance of salvation, testimony prayer meetings where men and women spoke about their experience with God, emotional prayer and new ways of structuring the Church), the New Mennonites never affirmed the second work of grace holiness doctrine so prominent early in the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church era.2 It is clear in the minutes of the York and Ontario Counties New Mennonite Society, that accepting the second blessing theology was a struggle for a number of the Markham leaders after the 1875 merger.3 It may have been too much of a stretch for other preachers such as Daniel Hoch in The Twenty, Christian Troyer in Markham who soon behaved as an independent evangelist, or Abraham Z Detweiler of Doon, Waterloo County, who never joined the United Mennonite Church and died a Methodist (listing himself in the Canada census as such already in 1881).

2. Regional membership. Especially for the Markham New Mennonites, but also true in Waterloo and Oxford Counties, the New Mennonite Church maintained some distinctive Mennonite organizational features. For one, the whole membership in Vaughan, Markham, Whitchurch, East Gwillimbury, Scott and Pickering Townships saw themselves as one society, and though Sunday meetings were sited in various locations, those were just local “condensations,” so to speak, of the regional church. The Minutes kept just one membership list for people who met at all these sites. People were not members at Dickson Hill as opposed to Bethesda, though habit would lead to closer identification with a geographic location, as it was later.4 Maybe in post-modernism, we are returning to regional churches again with satellite congregations?

Regional records. In southern Waterloo County, the “Minutes of the New Mennonite Society of Blair, Ontario, 1869-1874,” records members from North Dumfries and Wilmot Townships, and Doon in Waterloo Township.5 There were probably similar records for northern Waterloo at Bloomingdale/Breslau, but unfortunately, they may have been lost when the safe they may have been kept in was stolen in the late 20th century and never recovered.6 If Daniel Hoch’s small group in The Twenty (Jordan), Lincoln County, kept minutes, they have not survived either. The Mennonite Archives of Ontario preserves a number of writings by Daniel Hoch, however.

The regional mentality struck me as I learned more about the habits of Mennonites in Waterloo, who seemed to feel themselves members of a regional Church. They probably felt just at home attending preaching at, for example, Schneider’s (Bloomingdale), Cressman’s (Breslau), Hagey’s (Preston), Eby’s (Berlin) or Wanner’s (Hespeler) meeting houses on the east of Berlin as was convenient for them.7 Jasper Huffman lists infrequent meetings at one location as one evidence of “spiritual life being at a rather low ebb” in the Mennonite Conferences, but that overlooks the regional services generally available.8 The MBiC itself could not supply preachers every Sunday to all its “preaching points” either. They did have frequent weekday home (“cottage”) prayer meetings the main Mennonite groups did not practice, however.

Regional business. The NMC also continued semi-annual conferences to handle administrative and community concerns. The Markham New Mennonites experimented briefly with quarterly communion services, in the Methodist custom, but soon returned to the twice a year habit of many Mennonites.9

3. Another Mennonite carry-over was that the New Mennonite preachers were almost all farmer-preachers.10 None were paid, except some expenses—even in the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church (after 1883) salaried pastors came in gradually.11 The NMC preachers were chosen from a locality, continued to farm or conduct their work there and traveled on Sundays to preach at their assigned meeting points—usually not very far. They were “itinerant” in that they traveled on a weekend, but they were not itinerants in the Methodist sense, who moved to new “circuits” every few years where they lived and became ministers-in-charge. When the United Mennonites adopted the Evangelical Association (Methodist) polity between 1876 and 1878, the new rules were very hard for the generally older and farm-owning New Mennonite preachers. Most of them tried to be itinerants a few times, but to uproot their large families and abandon their farms was too much for most of them. Most became “local preachers,” or helpers, especially in the larger multi-appointment circuits, where their presence was appreciated for the rest of their lifetimes.

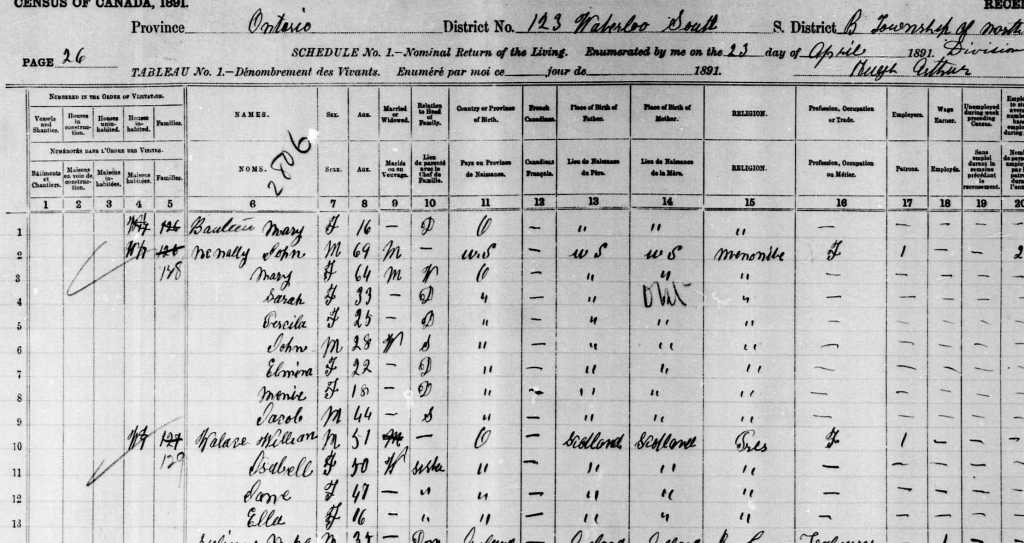

Credit: Library and Archives Canada

4. The NMC did not choose their ministers by lot, the way some Mennonite congregations did,12 but expected some sense of an evangelical-style “call from God” to serve. Joseph Raymer in Markham, and Amos Bowman in Port Elgin, hesitated to accept full responsibilities as preachers for precisely the reason they were not assured of a call (by God) to the ministry.13 The York County NM Society elected Caspar Wideman from Bethesda in Whitchurch Township to be ordained on resolution at a conference, not by lot.14 John McCauley was elected at Blair in the same way.

5. As pointed out by Sam Steiner, the New Mennonites were disturbed by the question of open or close communion.15 The widespread practice of 19th century denominations was “close” communion16 in which only full members of the church were allowed to participate in the Lord’s Supper of the church. There seems to have been a desire of many NMC ministers to allow open communion, but Daniel Hoch was against it. A statement made by an NMC conference in 1855 which supposed close communion, led several ministers to resign from the NMC. Further discussion led to a compromise the next year, and some ministers, such as John McNally, returned in 1857. Abraham Sherk left permanently, initially to the United Brethren in Christ.17 Daniel Hoch participated with the NMC but he experienced this and other frictions with the body he largely established.18

6. Some would call it “different visions” of how the New Mennonite Church should proceed in the early 1870s. Daniel Hoch was determined to remain Mennonite in doctrine, whereas some of his fellow New Mennonites were less committed, with other priorities. Perhaps agreement to use the Mennonite Dordrecht Confession of 1632 in the union of 1875 was a concession to Hoch’s desires.

Credit: A James Rennie, Louth Township, Its People and Past (1967) p 51.

Many in the NMC wanted to keep fellowship with both the developing Oberholtzer Church which was to become the General Conference Mennonites, and its breakaway Evangelical Mennonite Church lead by William Gehman.19 The Mennonite Conference of Canada attempted a reconciliation with Daniel Hoch and the New Mennonites in 1869, which foundered on the NMC’s and his insistence on certain pre-conditions and apologies.20 The group Hoch and his brother led at Jordan disbanded in 1870.21 Neither he nor his brother Jacob (d 1876) participated in the merger of the NMC in 1875 with the Reforming Mennonites. The resulting United Mennonite Church led by Solomon Eby and Daniel Brenneman, wanted open communion and it was ready to adopt still more revivalist practices.22 Hoch died in 1878 alienated from the United Mennonites, according to Samuel Steiner.23 The Evangelical Association pastor in Campden, ON, conducted his funeral.

Courtesy Missionary Church Historical Trust

In the year after Hoch’s death, Menno Bowman, based at Sherkston, visited Jordan and The Twenty, and started gathering new Mennonites (in the informal sense) and organized a “class.” The Evangelical United Mennonites (successor to the United Mennonites) resumed using the Mennonite Conference building at Jordan. By 1881 the EUM Twenty community constructed their own plain Mennonite structure, which they called “Bethesda,” at a site that became Vineland in 1894. Some kept meeting at Jordan (called “Zion”) making a two-point field.24 A strong MBiC community resulted.

Banner: grave of Abraham Ziegler Detweiler (or Detwiler) and his first wife Rachel Bechtel and some of their children, at Old Blair Cemetery, Blair, ON. Photo by author, June 2024

1Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online: Peter Geiger, John McNally, Abraham Raymer, Joseph Raymer, Samuel Schlichter, John Hoover Steckley, Christian Troyer Jr.

2Samuel J Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands: A Religious History of Mennonites in Ontario (Kitchener, ON/ Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2015), p 108.

3“Minutes of the New Mennonite Society of York and Ontario Counties 1863-1881,” Box 1010 MCHT.

4The process was fairly complete by the time congregations wrote their centennial histories in the later part of the 20th century: each focused narrowly on the life of the one location, with little notice that they once had a more regional perspective.

5Published in Mennogesprach (1987) Vol 5:2 and (1988) Vol 6:1; in Mennonite Archives of Ontario, and online. Note Waterloo County contained a Waterloo Township.

6Personal communication from Carol Blake of Breslau, January 10 2018. What look like quotes from the missing Quarterly Conference minutes of the circuit begin in 1884 in Ted Losch and others, Breslau Missionary Church 1882-1982 100th Anniversary (Breslau, ON: Breslau Missionary Church, 1982) starting on p [15] (my pagination).

7Some Waterloo County diarists roamed the County attending services as convenient for them, for example, Elias Eby (1810-1878), diary covers 1872-1878. https://uwaterloo.ca/mennonite-archives-ontario/discrete-single-items/diaries. Regional attendance patterns are described fictionally in A I Hunspurger, Nineteen Nineteen (Kitchener, ON: Ainsworth Press, ca 1980) or Mabel Dunham, Kristli’s Trees (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1948).

8Jasper A Huffman, ed, History of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church (New Carlisle, OH: Bethel Publishing, 1920) p 36.

9“Minutes of the New Mennonite Society of York and Ontario Counties 1864-1881,” Box 1010 MCHT. I will look at Mennonite and early EMCC worship habits in later blogs.

10Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, p 108, says they explicitly rejected Evangelical Association polity. A Z Detweiler from Doon was a bit of an industrialist, being partner in an iron foundry at Elmira and then Preston.

11Huffman, p 154-156.

12 Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, p 63.

13Raymer and Bowman: reports in “Minutes of the Canada Conference of the United Mennonite Church at Nottawasaga, Simcoe County, 5-7 June, 1878.” Photocopy in Ken Wideman Collection, Box 6020 MCHT.

14Half-yearly meeting minutes of April 23, 1873, “Minutes of the New Mennonite Society of York and Ontario Counties,” in Dickson Hill file, Box 1010 MCHT.

15Details in Samuel J Steiner, “New Mennonite Church,” GAMEO (2010) https://gameo.org/index.php?title=New_Mennonite_Church_of_Canada_West .

16My church history professor Dr C Mark Steinacher at McMaster Divinity College pointed out the term “close” communion is correct. People say “closed” by an understandable folk etymology.

17Michael G Sherk, “A Memoir of Rev. A. B. Sherk,” Waterloo Historical Society 4 (1916) p 35-36 with a photo of A B Sherk following, unpaginated.

18Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, p 116.

19The issues are reported in the MBiC Doctrines and Discipline in the historical introduction, for example, p 7 in the edition of 1924.

20Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, p 116-117.

21 https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Jordan_Mennonite_Church_(Jordan,_Ontario,_Canada).

22Daniel Brenneman, “Open Communion,” Gospel Banner editorial May 1879. Some who were initially in favour of the revival dropped out, for example, Daniel Wismer and the Bloomingdale preacher, Moses Erb. Erb did not join the New Mennonites and Daniel Wismer was uneasy with open communion and reconciled with the Mennonite Conference by 1877; Huffman, p 44.

23Samuel J Steiner, (2010), https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hoch,_Daniel_(1805-1878)

24Skip Gillham, ed, The Church on the Hill: Vineland Missionary Church 1881-1981 (Vineland, ON: Vineland Missionary Church, 1981) p 6-7.

Leave a comment