16. MBiC worship patterns. The leaders of what became the MBiC in Ontario were converted in testimony, prayer or protracted meetings (later called revivals), not in their Sunday Mennonite worship services. When they had to organize their own Sunday worship meetings as new denominations, they introduced the lively, spontaneous, emotional practices of the revival services as the desired normal worship experience. They did not use the word “liturgy.” Written liturgies were understood in the movement as a sign of “cold,” non-Spirit-led, “man-made” religion and therefore to be avoided.

17. Of course, to anyone who observes evangelical or “free church” services, there are frequently unwritten patterns of worship that are predictable in their “spontaneity.” Predictability could be as true of charismatic worship services as of holiness churches. As Pentecostal scholar Simon Chan wrote, “When one has been in charismatic churches long enough, one notices that prophecies and tongues occur at predictable moments.”1 The present writer has noticed the same phenomenon.

In Black Creek Pioneer Village, Toronto.

Credit: https://blackcreek.ca/buildings/mennonite-meeting-house/

18. Signs of Mennonite origins. The Mennonite origin of the MBiC worship pattern was also visible in the “amen corners,” now abandoned as a practice, that recent Missionary Church local history books in Ontario record as curiosities. Whereas in the 1860s, the other ministers in a Mennonite service would testify to the truth of the main sermon afterwards, elders or deacons in the MBiC services, sitting in those very same seats, would affirm the sermon during its delivery with shouts of “Glory!” “Hallelujah!” “Amen!” or still other short phrases. Here is one description of the arrangement of seating from one location on the large Markham field in York County, Ontario, Canada, which had several meeting places:

“In the early [late 19th -century] church, the pews were arranged in three sections; long benches in the centre, two aisles with the ends of the side seats attached to the walls. The front corners on each side called Amen Corners, had benches flanking the pulpit platform. These were for the elderly, hard of hearing or for visiting ministers, who would lend support to the speaker with a hearty “Amen” or “that’s right, brother!”2 [emphasis in the original]”

When the 1970s student revival in Nigeria spread to the UMCA in the 1980s, the elders said to the youth that the missionaries never taught them to practice some of the demonstrative ways the revival encouraged, even as simple as shouting “Amen!”3 MBiC Foreign Mission Board missionary Charles Tobias (“C T”) Homuth was known in Canada as “shouting Charlie;” what he did in Nigeria in his several terms (1903-1904, 1911-1913, 1915-1918) is not recorded.4 Early camp meeting and protracted meeting records in the Gospel Banner such as Presiding Elders’ (district superintendents’) reports, for example, those of Menno Bowman and Samuel Goudie, mention praises being shouted. Elder (“Reverend”) Moses Weber’s wife Christina (Sherk) Weber was remembered as a “shouting Mennonite” as well.5 Why the missionaries did not transmit such a simple worship practice is unknown. It has returned in some churches in some services in North American Missionary churches, but probably under the influence of the charismatic movement. However, I first heard such shouts from a former Free Methodist member in my home church in North Bay in the 1960s, and was encouraged to speak out in Riverside EM Church, Toronto, in the 1980s, which had Caribbean-origin members. Riverside joined the EMCC in 1983. Some American black, Caribbean or Hispanic church experiences may sometimes be imitated today. Another Nigerian revival practice is “general prayer” when everybody said or shouted their prayers at the same time, sometimes in tongues. Something like this was practiced by the MBiC or UMS missionaries, though perhaps it was silent or murmured.

19. Architecture. God willing, I will examine Missionary Church architecture more in later blogs of “EMCC History,” except here I will look at seating and benches.

20. Many Mennonite meeting places were designed with separate entrances for men and women, because they also sat separately. MBiC meetings gradually abandoned the custom of sitting separately. The short physical dividers down the middle in some early meeting places were removed and families tended to sit together by about 1920. In the large rural congregation of Vineland, it was not until the pastorate of Alfred G Warder (1913-1917) that the divider was removed.6 In the urban Bethany Church in Kitchener, it was gone some years before 1908.7 Many UMCA congregations of new converts separate the sexes where culturally appropriate to this day, as also happens in the United Missionary Church of India, I believe, another denomination raised up with UMS help after 1924.

Wesleyan Church, Gujarat, India. This congregation has received persecution. Credit: Surinder Kaur, Christianity Today, November 2023

21. Benches/ Altars. One of my blog respondents, Dr Dennis Engbrecht, tells me that to some Missionary Church leaders, the Church for a long time would have been an “altar-focused” church8 rather than pulpit, or music-stand oriented, as it is in many congregations today. The preachers attempted to get as many as possible to the prayer benches in the meeting place or the camp meeting tabernacle. This is a good insight.

Copying the evangelistic practices of 19th-century evangelists, many MBiC meetings had benches at the front of the hall where people were invited to come to kneel and “pray through” to forgiveness, assurance of salvation, restoration from backsliding or finding the experience of sanctification. The altar was sometimes called a “mourners’ bench,” (Methodism) where people were invited to come to repent of their sins, or the “penitent’s form,” (Salvation Army). Cyrus N Good’s account of a revival held in what is now Kitchener in 1894 mentions the use of the benches:

“Bro. [Henry] Goudie felt that another invitation should be given. He called on me to sing a chorus. The Holy Spirit immediately took over. We sang just a few lines of the Hymn, ‘My Lord, What a Morning when the Stars Begin to Fall!’ Instead of the stars falling, the Holy Spirit fell upon the congregation…Christians dropped to their knees and what a volume of prayer and calling upon God. Sinners ran to the altar…”9

In addition, the bench area might be used for congregational prayer on their knees for any need, healing or intercession. The living sacrifice of one’s body (Romans 12:1-2) was behind this language. The benches might be called “altars,” but this should not be confused with liturgical churches’ altars for the Eucharist or altar railings where communion elements were received.

22. Conclusions. Nature of public worship in the Nigerian UMS. Missionaries went to Nigeria with all these practices in their minds. For many years, before there were believers in the areas assigned to the Mission, they constantly conducted evangelistic/ preaching services at the mission stations, compounds or markets. Camp meetings were not introduced for decades.10 Bible readings, preaching, praying and singing were their common practices in public places. In time, further practices were selected from all those mentioned in the Bible, for example, modesty in clothing (according to North American standards), head covering for women in worship, uncovered heads for men, monogamy, tithing, dedication of children, laying on of hands, anointing with oil with prayer for healing, and fasting.

Special things, places, times? They did not introduce the literal “kiss of peace” which Paul refers to at the end of some of his letters, or taking handkerchiefs (now called “prayer cloths” by some, though that term is not in the Bible) which had touched holy people to heal the sick, the way some Pentecostals/ charismatics did and do imitating a report in the book of Acts (19:12).11 They stopped all literal sacrifices of animals, and forbade calling the communion a sacrifice or oblation, according to the usual Reformation doctrine that Christ has completed the sacrifice for sins once for all (Hebrews 9:12). They did not practice removing shoes while on holy ground: they did not see any ground as more holy than any other after the OT. (Some denominations founded in Nigeria picked up the occasional OT practice and do worship in bare feet.) For the same reason, they practiced no pilgrimages: one may meet God in any place. There were strictly, except for a Lord’s Day Sabbath, no “holy times,” either (Romans 14:5-6). Some observances, such as Christmas and Easter were noticed, probably by assimilation to European culture. Signs of the Methodist custom of “watchnight” (New Years’ eve) services appear in MBiC leader Samuel Goudie’s and missionaries Alex W Banfield and Cornelia Pannabecker’s diaries, although that time of year, too, has no specific biblical foundation for celebration. These customs were used to renew their covenant with or dedication to Christ. 12

23. The purpose of worship services. Instead, the UMS missionaries were aiming to lead people to repentance and faith in Jesus. For believers, services were meant to get people “happy, blessed,” or “feel the presence of God,” immediately, and in every service. Hustad says they were designed to produce “feelings of spirituality.”13 They preached for conversion and after that, for consecration to a process and crisis of sanctification. Even after the first few conversions, the preaching emphasis was always on evangelism and holy living. They had few set forms to bring to Nigeria, because the tradition of plainness (in their eyes at least) of buildings, times, ceremonies, order of service, decorations, clothing, symbolism, and architecture gave them very few and brief set forms. Their doctrine of the Holy Spirit encouraged them to believe he would lead the church at worship in liberty, as they called it. I should add, they did not call any church leader “Father,” as all were brothers and sisters, obeying Jesus (Matthew 23:9). Nigerian Christians will have to sort out this out with their culture of respect in addressing senior men and women in and out of church life.

24. The Lord’s Supper could not be conducted except among believers of course: the missionaries by themselves or at conferences. For these Bible-believing Christians, the words of Christ instituting the observance “as oft as ye drink this cup,” (I Corinthians 11:23-29 KJV), were all the liturgy the church needed.14 The Discipline did have a paragraph on the manner of receiving the elements.15 This may have been an inheritance from the teaching of the Swiss Brethren as far back as 1524. In a letter to Thomas Muntzer, Conrad Grebel wrote,

“The Lord’s Supper was ordained by the Lord as a means of fellowship. Nothing more or less should be used than the words found in Matthew 26, Mark 14, Luke 22 and I Corinthians 11.”16

Everything else, however rich in accumulated meaning in the centuries after the New Testament, was entirely unnecessary to these Bible-following people.17

25. Baptism. After 1888, the MBiC assumed the mode of baptizing was by immersion. The first MBiC baptisms in Nigeria were conducted for believers by Charles Homuth at Jebba in the Niger River by immersion in May and October 1913.18 The missionaries may have supplied clothing in some instances to people not used to, or affording, European or Muslim styles of clothing. Again, the words of Jesus at the end of Matthew’s gospel was considered to be sufficient liturgy. “I baptize you in the name [not names] of the Father, Son and Holy Ghost.” The emphasis in the Discipline was entirely on questioning the candidates on 1) their testimony of repentance and faith, and enjoying peace with God, 2) “willingness to renounce the world with all sinful gratifications,” and 3) willing to be taught from the Word of God and yield obedience.19 Yoruba Baptists from farther south were living along the Niger River at Jebba, and their baptism by immersion of believers was already known. In contrast, Anglican christenings of infants by pouring water had been conducted for more than a generation in the area.20

It should be noted that the UMS’ difficulty in providing elders in Nigeria, with an ordination thought to be necessary for leading the Lord’s Supper (a rule introduced for decency and order), meant that numerous Nigerian UMS members could live for years without participating in the ordinances.21 Their discipleship would then seem to be unconnected to observing the Supper. To this day, many UMCA members look on Holy Communion as a ceremony for advanced or at least older believers, a serious weakness in the UMS transmission of the faith and a weakness in UMCA spiritual formation.

26. Washing the Saints’ Feet. Covered in an EMCC History blog of that name.

27. Summaries.

- MBiC Foreign Mission Board and UMS missionaries continued the practice of biblical plainness and humility that their Mennonite and Wesleyan holiness theology taught.

- Their worship services were directed to evangelistic ends which they thought led to the praise and glory of God. The Lord’s Supper was not the focus of worship.

- They wanted to “feel” or “sense” the presence of God in worship by the practices they did follow, even though feeling and sensing words are not used in most Bible translations in connection with public worship.

- Despite their acceptance of emotional piety, the MBiC/ UMC did not achieve a theology that fully recognized that when human beings worship, the worshipers and “all that is within” them, soul and body, might worship in spirit and in truth.

- Their ideas about depending on the Holy Spirit in worship made them think that liturgies are only man-made because such liturgies were not clearly visible in the Bible, however ancient, or however skillfully done.

- In contrast, I fully accept that the Holy Spirit can guide the preacher in sermon preparation days or weeks before the day of delivery of the sermon. And if this is true, then the Spirit is fully able to help, for example, a person such as the English Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556) compose biblically true, wise prayers or forms of worship for churches that will receive them, for what became the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Why not? The key question is, are they useful for today and are they biblical in content? What is the true distinction between “man-made” and “Spirit-led” when a person prays for guidance? Of course the Holy Spirit has freedom to intervene. I do not accept the teaching that there is a significant difference in the NT between logos and rhema words of God, as promoted by some.

- The Missionary Church family of denominations (EMCC, Missionary Church USA, UMCA, and others) desire the work of the Holy Spirit to be visible in them. On the other hand, they sometimes have difficulty guarding themselves theologically against claims of the Holy Spirit’s leadership which introduce bizarre behaviour or teachings.

- They would however, support the idea that Nigerian believers should get their ideas and practices about worship from the Bible and their experiences of God, not just from the missionaries.

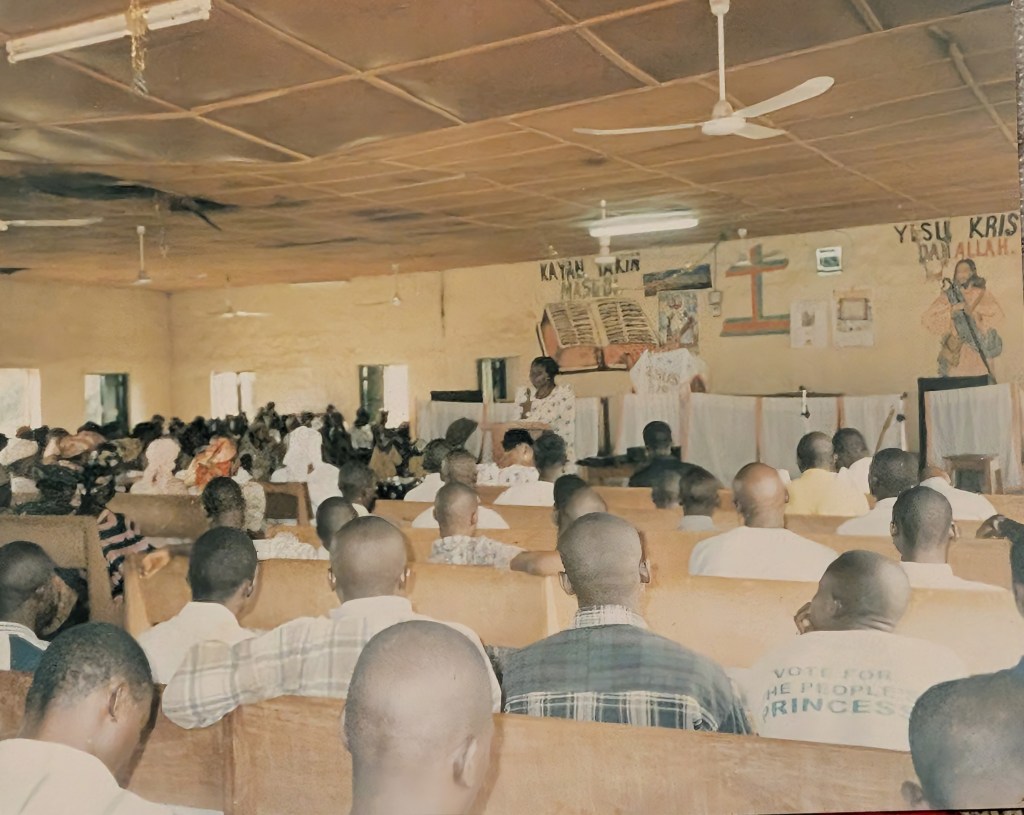

Banner: English service, UMCA Magajiya, Nigeria, 1999. Courtesy: Fuller Family Collection.

1Simon Chan, Liturgical Theology: The Church as Worshiping Community (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006) p 127.

2Clarence McDowell and others, Built in this Place: Centennial 1877-1977, Markham Missionary Church (Markham, ON: Markham Missionary Church, 1977) p 34. The same report comes from the early days of the Bethel circuit at New Dundee, Waterloo County, Ontario: Muriel I Hoover, A History of Bethel Missionary Church (New Dundee, ON: Bethel Missionary Church, 1978) p 10.Similar to the narrative in Eileen Lageer, Merging Streams: Story of the Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1979) p 30.

3Personal communication, Maidawa Tari, one-time UMCA General-Secretary from Magajiya, Niger State.

4Letter of C T Homuth to Everek R Storms, July 28 1952, in Storms Collection, Missionary Church Inc Archives, Mishawaka, IN.

5McDowell, p 35. The Missionary Church Historical Trust collection has Christina’s family’s Bible.

6Skip Gillham, ed, The Church on the Hill: Vineland Missionary Church 1881-1981 (Vineland, ON: Vineland Missionary Church, 1981) p 11.

7Ward M Shantz, A History of Bethany Missionary Church 1877-1977 (Kitchener, ON: Bethany Missionary Church, 1977) p 6.

8Personal communication from Dennis Engbrecht, April 13 2025. The remark came from District Superintendent Terry Powell.

9Quoted in Shantz, p 11-12.

10Some missionaries, such as Stella Lantz from the Nebraska Conference stationed at Jebba, mentioned how much they missed the energy of camp meetings.

11This is a result of Pentecostals treating selected events in Acts as prescriptive/ normative rather than historical/ descriptive. The topic is one of lively debate in biblical interpretation.

12Goudie: “Diary,” December 31, 1903, in Berlin, Ontario, in Eleanor (Goudie) Bunker Collection; Pannabecker: “Diary,” December 31, 1912 in Jebba, Nigeria, photocopy in MCHT, Box 3012; Banfield did not have a watchnight service to attend at Garkida, Nigeria, December 31, 1929, but on January 1, 1930, he wrote,”Re-consecrated my life to the Service of Jesus Christ my Lord,” “Missionary Tour from Lagos to Bornu, Sokoto, and Return,” (no date) p 18, typescript in Missionary Church Inc. Archives, Mishawaka, Indiana. “Watchnight service,” Wikipedia. Accessed April 30, 2019.

13Donald P Hustad, Jubilate II: Church Music in Worship and Renewal 2nd ed (Carol Stream, IL: Hope Publishing, 1993) p 235.

14In the catechism of Samuel Goudie, ed, Book of Religious Instruction ([Kitchener], ON: Executive Committee of the MBiC Church, 1933) p 75-76, the answer to “In what manner and with what words did the Lord institute the holy communion?” came entirely from I Corinthians 11:23-25.

15MBiC Doctrines and Disciplines (1924) p 44.

16As quoted in Cornelius Krahn and John D Rempel. “Communion.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 17 Apr 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Communion&oldid=162901.

17Chan, throughout, demonstrates the undeniable richness of symbolic and scriptural reference in the developing liturgy of the early church from the 2nd century AD onward. But it is all extra to the Bible.

18Everek R Storms, What God Hath Wrought: The Foreign Missionary Efforts of the United Missionary Society (Springfield, OH: United Missionary Society, 1948) p 36.

19MBiC Doctrines and Disciplines (1924) p 43.

20References in James Clare Fuller, “We Trust God will Own His Word: A Holiness-Mennonite Mission in Nigeria 1905-1978,” MTh thesis for McMaster Divinity College, Hamilton, Ontario, 2003, p 83, note 66.

21Fuller, p 106-111.

Leave a comment