What is worship, after all?

Much has been written and preached in the last generation or two about worship. I have heard many talks and books recall the etymology of the English word: Old English “weorth-shipe,” ascribing worth or honour to those to whom honour was due, supremely, to God. This is helpful but does not go back to the Bible’s Hebrew or Greek words.

Dura Europos synagogue, 3rd century.

Credit: Wikimedia commons, public domain

My Hebrew is pretty minimal, but that usage can be studied through good OT reference books.1 Several NT Greek words are translated “worship,” or related ideas, mostly the proskuneo, sebomai, diakoneo, latreia and leitourgia word groups. The proskuneo group, often referring to “bowing down,” in act or metaphor, can mean showing reverent adoration in the presence of deity, with the imagery of submission and giving honour. Sebomai emphasized feeling awe and reverent fear. With diakoneo, Jesus’ followers in the NT saw no problem calling themselves serving as servants or even slaves of God.2 Priestly actions (sacrificing, offering gifts) are covered by latreia. The Bible leaves us with a puzzle in Revelation 22:3, where the Greek word for our activity in the new Heaven and the new Earth is latreusousin-which could be translated as either “they will serve” or “they will worship.” I suppose some will say, why not both?3 The leitourgia group suggests “service.” In classical times the words commonly meant “public service” for a city. The KJV often translated the group with “ministry” words.

Response. Many people who have reflected on Christian personal and corporate worship agree, as James Robinson does, that worship is response:

“It is the human response to the divine nature…Man’s response is itself divinely inspired…Worship can only rightly be offered to God himself…The heart of Christian worship is adoration…The worship service is a tryst with God…Worship involves the whole man. It cannot be divorced from moral and ethical content…Ps 24:3-4.”4

Being and doing. We express ourselves awkwardly these days, I think, by praising God with the phrases “who he is,” or “who you are.” We should be able to use more concrete words for God’s excellent character, nature, essence or attributes, not these stopgap phrases. Christian worshipers should be comfortable speaking of God’s love, wisdom, goodness and anger (against sin) and much more.

But not only is our worship a response to God’s being, it is especially to God’s initiative, his acts for us, redemption at the Red Sea or supremely on the cross. Some liturgical scholars see God giving and worshipers responding in every biblical worship interaction.5 Augustus Strong, a Baptist theologian of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, approved of this double action. “In it God speaks to man [reading of Scripture and preaching] and man to God [prayer and song].”6 It is not easy for me to see that what God has done or does can be called worship as such, but that seems to be what these writers mean. Certainly God has done great things in Christ, and the reading of Scriptures and preaching proclaim that.7 And proclaiming God’s pardon is performative to an extent. To liturgists, the Lord’s Table is the supreme moment of God acting, not just for us supplying the bread and fruit of the vine, and remembering Christ on the cross, but God giving in the present. I don’t see it quite that way.

Where to begin? The initiative of God is often depicted in public worship by a suitable reading of the Word of God very early, if not as the first action of the service. Often this is conducted as a Call to Worship (we are invited to gather essentially by God, and so constituted, respond) or by the different notion of Invocation (we acknowledge God’s presence and invite him to lead us where he wills). I heard about calls to worship somewhere in my reading as a young theological student and determined to begin every service I planned with some form of call to worship by Scripture.8 I don’t think many modern EMCC churches do this, but I could be wrong. Many churches begin worship services, it seems, by greeting the worshipers (“Good morning, Church!”), and then maybe God.

Is there a centre? A further question is whether we can discern what is the centre of human response to God. Some define worship so broadly that service (obedience to God’s will) is a subset,9 while others see that service is the broad biblical category, with worship more narrowly as one part of our service, as the English Methodist I Howard Marshall insisted, “To be sure, worship is part of the church’s service to God (Heb 13:15; cf. Rev. 5:11-14; 7:9-12). But it is not the whole of it. [I]t must be insisted that the church’s primary task is not to worship God but to serve God…” (emphasis his).10

Pulpit or music stand. I saw another choice graphically displayed as I returned from missionary tours over the years 1992 to 2010. The pulpit (depicting the centrality of the Word) was gradually displaced by the music stand (representing to many the priority of worship, narrowly defined, or at least signaling music, the 21st century emphasis) in the practical theology of my Kitchener membership congregation. One pastor asked me about this tendency to displace the pulpit and I gave my opinion that the Word was central since Reformation times, and I saw the pulpit restored on my next visit to Canada. But it didn’t last after that pastor left. The music stand prevailed, as it has nearly everywhere in evangelical-type churches. This is a major theological shift. A popular worship song declares the heart of worship is “All about Jesus,” which is not very definitive, but not bad if it is set in a full Trinitarian theology.11 God evokes response. And Jesus is the Word of God.

Courtesy: Fuller family photography

Gareth Goossen has been serving in a Mennonite Brethren congregation, and is a musician and a Waterloo Region worship leader. He cautioned about the current dominance of music as the main way to worship corporately.12 I wince when a worship leader says, “OK now, let’s begin to worship the Lord,” when I thought we had already been worshiping the Lord. What were we doing in prayer and Scripture reading? Even announcements can be worship, as I mention in EMCC History “We Worship Part 2.” American Missionary Church theologian Jared Gerig said, “…singing, praising God, praying, the Lord’s supper, giving, preaching, meditating, and thanksgiving can all be God-directed and for his Glory. This is worship.”13

What is worship, again? James White believes, rather broadly, we can define Christian worship phenomenologically, by analyzing what Christians “do” in worship. In other words, he avoids temporarily at least, deciding what is central. He could justify all these Christian habits biblically. His procedure is somewhat backward and may be human-centred, but is still helpful:

“We structure 1) time (days, weeks, years), and 2) space (places for actions); we provide 3) services of prayer and praise, we include 4) time for reading the Scriptures and preaching; we 5) bring people into the Body of Christ, and 6) we remember Jesus in the Eucharist; and 7) we conduct ceremonies for Christians in their life transitions.”14

You will notice no mention of music, though most could involve it. Though no one would deny the individual the possibility of private devotion/ worship, for White, worship is chiefly corporate.

Courtesy: Missionary Church Historical Trust

Many theologians and certainly sociologists believe religious worship is all about hallowing times, places, people, sounds and things.15 Currently, I would say, the trend to call the meeting hall a “sanctuary,” the church building “God’s house,” introduction of more and more practices of the “Church Year” time structure, recommendation of spiritual retreats and pilgrimages and so on, are signs of this human tendency. It is true many people find fresh devotion to Christ when they adopt this or that new practice of Lutheran, Anglican, Catholic or Eastern Orthodox church life, and sometimes they bring it into the free church worship services as something cool. The justification is that humans appropriately “embody” their worship. There is nothing especially wrong with many of these practices on their own, but they are really fragments of large culture-constructs that may have bent away from Scriptural direction, despite the appeals to the Bible that the churches might make for individual elements. Some people, impressed by the totality of those structures, leave their evangelical/ free church membership to join the other traditions.

Free church traditions resist this trend to make outward forms sacred.16 The “free churches” are usually said to be (in North America) Baptist, Mennonite, Evangelical Free, Alliance, Bible Church, Brethren and such. The EMCC, as a mix of Anabaptist, Evangelical, Wesleyan, Pietist and Keswick deeper life theology sits in the free church camp. In the current congregationalizing of North American church life, free church traditions have spread to many groups. Some churches flatten the landscape by saying everything is sacred in New Testament terms, so nothing is more sacred than others, as the Christian and Missionary Alliance editor and pastor A W Tozer insisted.17

Liturgical fragments. Those in the EMCC have had definite public worship patterns. In the United Missionary Church in North Bay, for years we sang the doxology of Thomas Ken, “Praise God from Whom all Blessings Flow” after the ushers had collected our offerings by passing plates through the pews.18 During communion, the organist almost always played the tune “Olivet” by Lowell Mason used with “My Faith Looks up to Thee,” (#405, Hymns for Worship). Again, the ushers passed the tray with individual communion cups, and plates with cut up grocery store bread. I did not hear concern about leaven in the loaves then.19 Much popular Christian art pictures rounded loaves obviously made with yeast. In earlier years MBiC deacons’ wives typically baked the bread the day before as part of the farm weekly bread production.20 These quasi-liturgical fragments, set in a generally “hymn sandwich” format, were probably worship habits our pastor Earl Pannabecker learned from his Kitchener home churches, Bethany and briefly, Evangel. How did those patterns begin?

Credit: Pexels, Theologos Christodoulou image

Beginning with a Mennonite Sunday worship pattern, the revived Mennonites (1850s-1883) that formed the core of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church added Methodist-style revivalism in prayer and camp meetings that modified their worship experience. Revivalism focused its energy on the evangelistic service, with time given to the invitation to turn to Jesus and to testimonies of spiritual experiences, whether that occurred on Sunday or in special evening services.

Hustad reports the typical pattern (except in the early Evangelical Association and EMCC, there were no choirs or soloists, as I have mentioned elsewhere):

Hymn (a group, often not related to each other or to the sermon, led by a “songleader”)

Prayer (brief)

Welcome and Announcements

Special Music (choir, solo or small group)

Offering

Solo

Sermon

Invitation (Hymn)

Dismissal (Benediction)21

Look familiar?

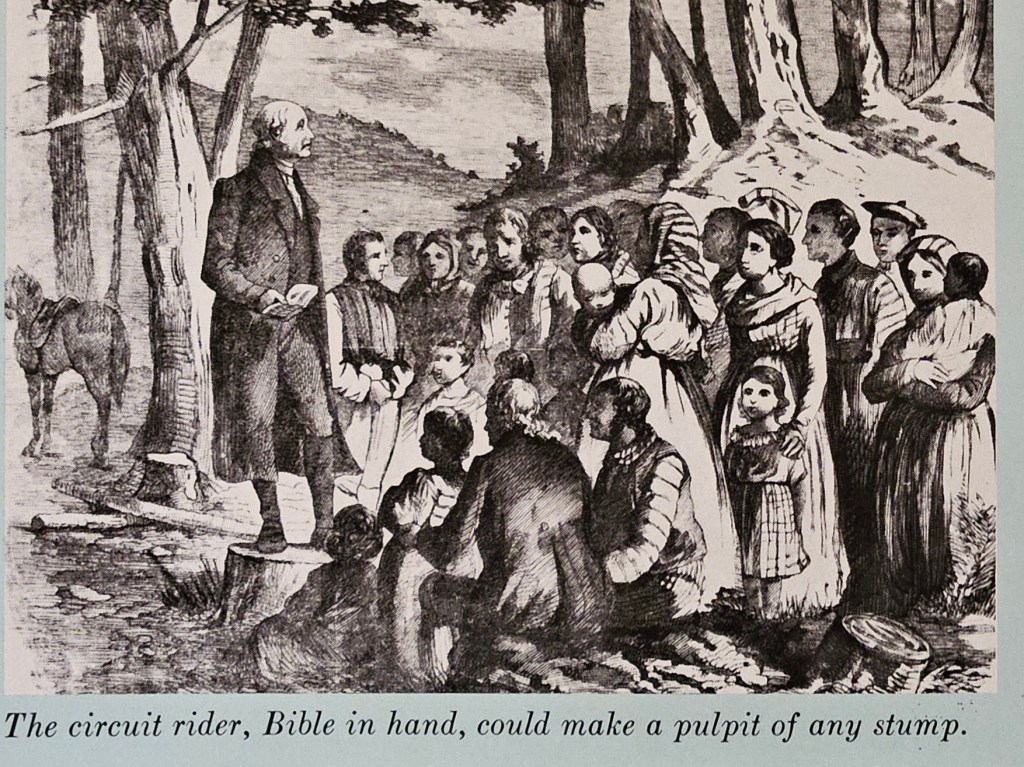

Banner: “The circuit rider, Bible in hand, could make a pulpit of any stump” Toronto Public Library, in William Kilbourn, ed, Religion in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1968) p 53.

1Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, or online aids.

2Lois K Fuller, “Slaves of God/ Sons of God,” UMTC Journal of Theological Studies Volume 1 (1995) p 41-46.

3Perplexingly, the scholar for the article on latreia in the Concise TDNT assigns the activity to the “adoration” side: H Strathmann, “latreuo, latreia” in Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich, ed, abridged by Geoffrey W Bromiley, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B Eerdmans, 1985) p 503-504.

4James Robinson, “Worship,” in S Taylor, ed, Beacon Dictionary of Theology (Kansas City, MI: Beacon Hill Press of Kansas City, 1983) p 551-552.

5James F White, Introduction to Christian Worship rev ed (Nashville, KT: Abingdon Press, 1990) p 25. See also Simon Chan, Liturgical Theology: The Church as Worshiping Community (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006) p 61.

6Quoted in Alliance theologian George P Pardington, Outline Studies in Christian Doctrine (Harrisburg, PA: Christian Publications, 1926) p 16.

7I Howard Marshall, Pocket Guide to Christian Beliefs 3rd ed (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1978) p 115.

8I think it was a book by James Hastings Nichols, Corporate Worship in the Reformed Tradition (Westminster Press, 1968). Reformed or not, it makes great sense to acknowledge the prior work of God before we respond in prayer or praise. A musical selection could, of course, feature Scripture at the start, just as a prayer, acknowledging God’s call to worship, could. There are many ways to acknowledge his priority.

9Gareth J Goossen, Worship Walk: Where Worship and Life Intersect rev ed (Breslau, ON: Make Us Holy Publishing, 2014) p 6.

10Marshall, p 115-116. Donald P Hustad agrees, Jubilate! Church Music in the Evangelical Tradition (Chicago, IL: Hope Publishing, 1981) p 64.

11Matt Redman, (1999) “I’m coming back to the heart of worship./ It’s all about you,/ All about you, Jesus.”

12Goossen, p 3.

13|Jared F Gerig, “The Church of Jesus Christ,” in Ralph E Ringenberg, ed, Believers in the Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1976) p 40.

14White, p 23-25.

15“Embodied worship.” Clark Pinnock in later years (McMaster Divinity College class notes 2002-3) observed special times, places, sensations and objects in his devotions; Michèle H Richman, Sacred Revolutions: Durkheim and the Collège de Sociologie (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002) p 1.

16Cf Hustad, p 118.

17Aiden W Tozer, Chapter 10, “The Sacrament of Living,” in The Pursuit of God (Harrisburg, PA: Christian Publications, 1948, reprint Moody, 2006) p 121-131.

18Anglican pastor and bishop Thomas Ken (1657-1711), “Praise God from whom all Blessings Flow,” hymn 569 in Hymns for Worship (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1963), sung to “Old One Hundredth.” A version of Ken’s longer hymn, from which this doxology was taken, was “All Praise to Thee, My God, This Night,” # 78 in the same hymnbook.

19Unleavened bread was prepared by a deacon’s wife on the Bethel field, Muriel I Hoover, A History of Bethel Missionary Church (New Dundee, ON: Bethel Missionary Church, 1978) p 14.

20Ward M Shantz, A History of Bethany Missionary Church (Kitchener, ON: Bethany Missionary Church, 1977) p 38.

21Hustad, p 158.

Leave a comment