The EMCC Sunday School is in decline at this writing, judging by annual reports, or lack of them, from congregations. (Beginning in 1986, more and more EMCC congregations failed to report their statistics, especially their Sunday School numbers.) The form of Sunday School has declined but some people would say it survives in small groups, children’s clubs and even online courses. However, a study of Bible engagement suggests any kind of Bible learning has seriously eroded in Canada.1

For over 100 years the Sunday School was a vigorous institution in the Mennonite Brethren in Christ/ United Missionary Church/ Missionary Church,2 as well as in the Evangelical Association churches in Ontario. One of the very first activities of Evangelical Association supporters in Ontario was to start a Sunday School in Berlin (Kitchener) way back in 1837.3 Sunday Schools in the EvA were then quite new, the first being in Pennsylvania in 1832, modeled after Methodist ones.4

So, how did Sunday Schools begin? How did they work? And can they work again? These are important questions.

Our EMCC history books usually list the desire for Sunday Schools as one of the reasons for the formation of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church when the main Mennonite Church was reluctant to encourage them.5 The New Mennonites of Canada West formed a Sunday School at Dickson’s Hill in Markham Township in the 1860s.6 One of Solomon Eby’s first actions in the Church in revival in Port Elgin, ON, was to start a Sunday School.7 When the New Mennonite Church and the Reforming Mennonite Society united in 1875, they passed a resolution vigorously recommending Sunday Schools.8

Mennonite histories qualify this situation, noting that the Wanner and Hagey meeting houses in Waterloo County each started a Sunday School in 1840, and Mennonite bishop Benjamin Eby began a Sunday School in Berlin (later called Kitchener) in 1841. Bishop Jacob Gross and preacher Dilman Moyer in The Twenty/ Jordan (in the area of later Vineland) on the Niagara peninsula started one in 1848.9 There were numerous experiments with something like Sunday Schools in Mennonite Conferences from 1840 to 1875, as Harold Bender said:

“During the decade of 1865-1875 Sunday schools were started in every [American] state where there were Mennonite or Amish congregations, and most Mennonite conferences took action approving Sunday schools. In that decade at least 35 permanent Sunday schools were established. By 1875 the victory had been won in substance…”10

Bender admitted that every Sunday School started before 1863 and many until about 1880 closed at some point largely because of opposition from inside the Mennonite Church.11 Opposition to the increasing use of Sunday Schools was one of the reasons for those who became Old Order Mennonites leaving US Mennonite conferences around 1872 and the Old Order splits in Ontario in 1889. Still, there was a rising desire for Sunday Schools throughout North American Mennonites. This seems proven. Mennonite bishops had been trying to avoid separations by going slowly.12 We need to be sympathetic to their situation. EMCC historians should change their tune on this one.

Credit: Scripture Press.

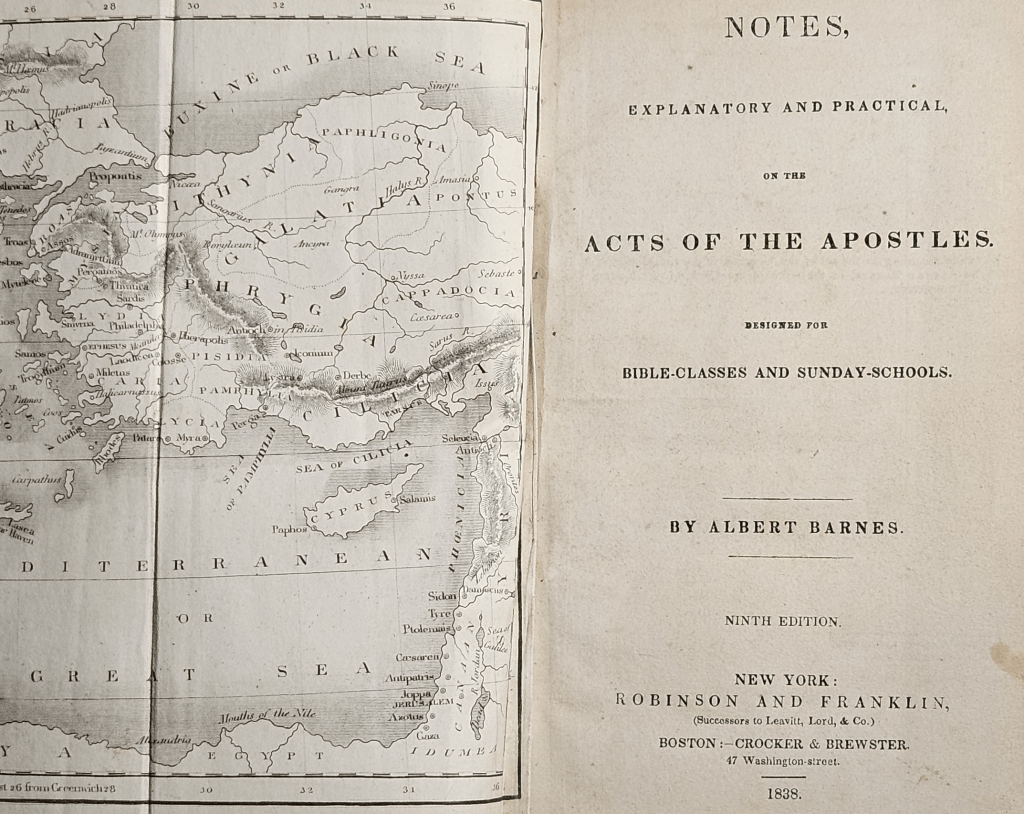

The Sunday School movement began in the UK in 1780 as a non-denominational series of institutions for working-class children.13 Methodists in the US probably adopted the idea quite early, but the American Sunday School Union (founded 1824) led in biblical and moral education in many American communities before the churches reached them. In my library I have a popular account of ASSU missionaries, The Prairie Missionary, telling anecdotes of their demanding labours up to 1853.14 I also have an example of their lesson books published in the 1860s.15 One of my favourite Bible commentary series, one by Presbyterian Albert Barnes, began as lesson helps for American Sunday School teachers. In the original preface of 1832, he said, “It was my wish to present to Sunday-school teachers a plain and simple explanation of the more common difficulties of the book which is their province to teach.”16

By 1844, major North American denominations were establishing their own Sunday School departments.17 Nevertheless, in Ontario, union Sunday Schools that met at different times than the worship services of the supporting churches, were quite common. Even the large Canadian Wesleyan Methodist Church as late as 1867 cooperated in 216 union Sunday Schools of its 721 schools.18 Many Mennonites encountered Sunday Schools in the same way.19 Amish in Waterloo County sometimes attended non-Mennonite Sunday schools, such as at the Wilmot Centre Evangelical Association congregation about 1860 (Orland Gingerich, The Amish in Canada (Kitchener, ON/ Scottdale PA: Herald Press, 1972) p 68 ). This was true for the MBiC.20 In Indiana, Daniel Brenneman’s church in Elkhart shared the conduct of a Sunday School with the Evangelical Association.21 Gormley, Blair, Dickson Hill, and others shared in Ontario not only a church building with other groups, but probably a Sunday School as well. The Altona MBiC shared a building and a Sunday School with the Christian Church from 1875 to 1956.22 At Shisler’s Point (part of the Sherkston field) on the north shore of Lake Erie, the MBiC shared with and later sold their share of the building to the Brethren in Christ, but held a joint Sunday School with them for many years.23

The MBiC’s precursors (1852-1883) pursued founding Sunday Schools and improving them. Early annual Conference reports started enumerating the number of Sunday Schools, new Sunday Schools started, enrollment, teachers appointed and actual attendance averages.24

In Canada, MBiC Sunday Schools commenced in exactly the period in which Canadian Sunday School teachers received increased attention for training, mainly through the Sabbath School Association of Canada.25 The Sunday School Union Society of Canada, founded in 1822, was succeeded by the Canadian Sunday School Union in 1838. The Sabbath School Association of Canada (which became the Sabbath School Association of Ontario) was established in 1863.26 Although as non-conforming Mennonites, the MBiC were reluctant to officially join any association of other Christian churches,27 the MBiC Sunday School supporters watched developments and imitated the activities of other Sunday Schools. During research for my biography of Sam Goudie, I noted he occasionally attended regional Sunday School Conventions, not sponsored by the MBiC, especially when he was pastor in Berlin (1900-1903), and found them useful.28

The American Sunday School Union starting in 1872, provided International Uniform lesson plans,29 which many denominations adopted, the Evangelical Association among them.30 The MBiC denominational magazine, the Gospel Banner, began printing Sunday School lessons following the International Sunday School Uniform lesson outlines, with details written by MBiC pastors. Later, Jasper A Huffman founded and edited the weekly Sunday School Banner from 1911 until about 1945, which some MBiC Sunday Schools used.31 The first full lessons I have found were printed in December 1892, and already included a lesson story by August F Stoltz, a Canada Conference elder from Mannheim, near Berlin.32 The annual Ministerial Conventions of preachers occasionally included essays on how to improve this or that aspect of Sunday Schools. The MBiC in Ontario was the first North American Mennonite group to hold a Conference-wide Sunday School Convention, at Breslau, in 1889.33 These cooperative events have disappeared in the totally fragmented Christian education environment of the 21st century.

Courtesy: Missionary Church Historical Trust

An instructive parallel to the Mennonite encounter with Sunday Schools is that of the Brethren in Christ. Here, too, was opposition, and simultaneously, approval by various members. Having a tradition of moving ahead through agreement in their General Conference, the BiC in Ontario did not hold their own Sunday Schools until after their 1885 General Conference approved them. This did not mean individual members had not already attended schools led by others, especially in Waterloo County, where the United Brethren in Christ and the Mennonite Brethren in Christ attracted some BiC members (in the MBiC case obviously only after 1875). BiC Congregations in Markham (York County), Bertie (Welland County) soon started their own Sunday Schools, and in other places which had some experience in community and union Sunday Schools, eg Wainfleet (Welland), and Sixth Line in Nottawasaga Township (Simcoe County).34

In the later 20th century, Mennonite theorists thought they discerned an implicit theology alien to Anabaptist principles in their imported Sunday School institutions and proposed alternatives, but when Harold Bender wrote his two works on the Sunday School (1940, 1959), he was an obvious enthusiast for the benefits of them to the Mennonite Church in those years.35 In our own years of EMCC Sunday School decline, we might consider these Mennonite critics and learn what we can from them about reviving our weakening engagement with God’s Word. Maybe there is an inherent weakness in an institution that does not obviously flow from parental instruction (eg Deuteronomy 6) or congregational (as distinct from age-grade segregation) discipleship. There is also obvious weakness in congregations doing whatever seems good in their own eyes when they could benefit from cooperation in their Canadian denomination. But that is another discussion.

Next article I will look at how the Sunday School plans of the MBiC, the United Missionary Church and the Missionary Church actually worked out.

Banner: Toronto’s Riverside (EM) Church Sunday School outing, ca 1986. Courtesy: Fuller Family collection.

1Rick Hiemstra, “Confidence, Conversation and Community: Bible Engagement in Canada, 2013,” through https://bibleleague.ca/bible-engagement-study/

2See EMCC History Page “Formation of the EMCC” for a review of the groups and process that produced the current Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada.

3J Henry Getz, ed, A Century in Canada: The Evangelical United Brethren Church (Kitchener, ON: Canada Conference of the Evangelical United Brethren Church, 1964) p 7.

4Raymond W Albright, A History of the Evangelical Church (Harrisburg, PA: Evangelical Press, 1942), p 190-191.

5Jasper A Huffman, ed, History of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church (New Carlisle, OH: Bethel Publishing, 1920) p 54, 150; Everek R Storms, History of the United Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1958) p 181. Eileen Lageer, Common Bonds: The Story of the Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada (Calgary, AB: Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada, 2004) p 80.

6Storms, p 182. See also Box 1010 MCHT, “Minutes of the New Mennonite Society of York and Ontario Counties.”

7Lageer, p 80. What year this was is not stated.

8Storms, p 182.

9Harold S Bender, “Sunday School,” Mennonite Encyclopedia Vol 4 (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1959) p 658, col b.

10Bender, ME, p 659 col a.

11Harold S Bender, Mennonite Sunday School Centennial 1840-1940: An Appreciation of our Sunday Schools (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1940) p 32.

12Bender, ME, p 658, col a-b.

13, Daryl Busby (2013), “Does the Sunday School have a Future in Canada? Reflections upon a Little School with a Big Story,” p 7. https://www.academia.edu/19323119/History_and_future_of_Sunday_School_in_Canada

14Mrs O S Powell, The Prairie Missionary (Philadelphia, PA: American Sunday School Union, 1853).

15Lessons for Every Sunday of the Year, from the New Testament: For Scholars of all Ages Series Two (New York: Carlton & Porter, 1863).

16Albert Barnes, Notes, Explanatory and Practical, on the Gospels: Designed for Sunday School Teachers and Bible Classes Vol 1 revised and corrected (New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1865) p 3.

17Bender (1940) p 23.

18John Webster Grant, A Profusion of Spires: Religion in Nineteenth-Century Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988) p 108.

19Bender (1940) p 12.

20Neil Semple, The Lord’s Dominion: The History of Canadian Methodism (Montreal, QC/ Kingston, ON: McGill-Queens University Press, 1996) p 369.

21This is one of those factoids I know I have seen somewhere, but can’t document now. Hopefully an EMCC History reader will know?

22Lillian Byer, Altona Christian-Missionary Church 1875-1975 (Altona, ON: Altona Missionary Church, 1975) p 3.

23E Morris Sider, Be in Christ: A Canadian Church Engages Heritage and Change (Oakville, ON: Be In Christ Church in Canada, 2019) p 53.

24As early as the report on that year’s Canada Conference; Gospel Banner (May 1 1887) p 9.

25 Patricia Kmiec, “‘Take This Normal Class Idea and Carry it Throughout the Land’: Sunday School Teacher Training in Ontario, 1870-1890,” Historical Studies in Education/ Revue d’histoire de l’education Special Issue [internet, nd, though after 2008]

26 Kmiec, p 197-198.

27The first group the Ontario MBiC joined was the inter-Mennonite Non-Resistant Relief Organization (NRRO) in January, 1918.

28Eg, Sam Goudie, “Diary,” October 28 1902. Goudie’s diaries quoted courtesy Eleanor (Goudie) Bunker Collection.

29Bender, ME, p 658, col a.

30Albright, p 297.

31N P Springer, “Sunday School Banner,” ME Vol IV, p 660 col b.

32August F Stoltz, “Lesson Story,” Gospel Banner (December 15 1892) 8. Beginning in 1893, the Gospel Banner increased its frequency from biweekly to weekly, so it was able to include more copy.

33Storms, p 274. Other Mennonites held their first general Sunday School conference in 1892; Bender (1940), p 24.

34Sider, p 183-184.

35Bender (1940) p 46-56, Bender, ME, p 658-659.

Leave a comment