North American Mennonites and Brethren in Christ1 mainly applied non-swearing of oaths2 to rejecting membership in “oath-bound secret societies.”3 In Ontario, this put them at odds with their non-Mennonite neighbours. Nearly every settlement in the province had one lodge or more operating.4 Mennonites objected to both the oaths and the secrecy as incompatible with followers of Christ Jesus. Further, many lodges and fraternal societies required loyalty to fellow members above all other relationships, setting aside the faithfulness required of believers to God and to members of the body of Christ.5 An additional offense would be that, as William Kostlevy demonstrated, most secret societies discriminated against women.6 Many Wesleyan holiness churches7 and Keswick/Higher Life groups8 also opposed secret societies.

Sometimes churches such as 19th-century Canadian Methodists objected to secret societies. One objection as reported by Canadian historian Neil Semple was not biblically-based, but simply concerned competition for the time of the Methodist minister trying to be a member of both the church and a fraternal society. Semple did note more seriously, however, that “Secret oaths and secret loyalties could lead to unlawful or unchristian behaviour.”9

Mennonites did not allow the word “could.” They were convinced the secrecy and demand for other loyalties were automatically non-Christian. The follower of Jesus is a brother or sister to all other believers first and foremost. Also, secrecy inevitably undermines trust, for example, in families or in government, as in countries where significant numbers don’t believe their government’s advice in medical matters, a direct result of the exposure of CIA-like secrecy and lying disavowals.

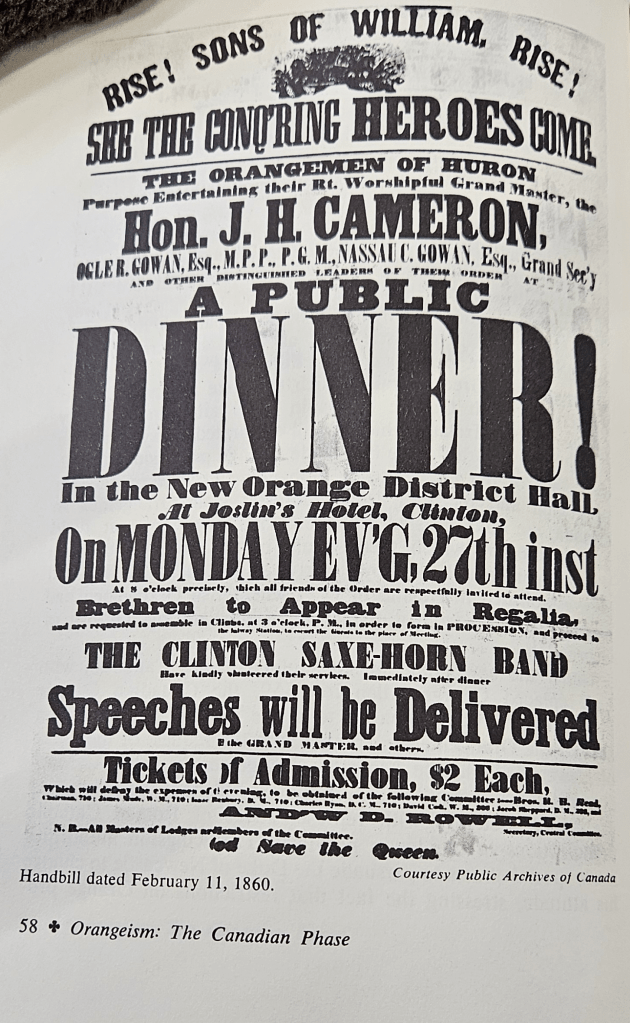

Public dinner, but secret ceremonies, militarism.

Credit: H Senior, Orangeism : The Canadian Phase (1972) p 58.

Eventually, so many Methodists became members of secret societies, their churches could no longer successfully object to lodges as a denomination.10 In the USA, the Free Methodist Church formed partly in response to Methodist Episcopal leaders’ compromising memberships in secret societies.11 A similar problem compromised Anglican membership, and doubtless this has been a problem for still other Canadian Christian communities, though some would not call it a problem. Roman Catholics often warned against the Freemasons precisely because for long periods Freemasons were in fact anti-Catholic, whatever they say now. American Baptist William Brackney studied Presbyterian and Baptist struggles in the eastern USA to defend against lodge influences.12 The United Brethren in Christ in North America were severely crippled in a controversy that split the church in the 1890s over secret societies. UB churches in Canada have remained at about 10-12 congregations for a century, unfortunately, partly due to the struggle.13

MBiC engagement with secret societies. In the MBiC/UMC, the church magazine reprinted controversies with secret societies as warnings. As an example, it reported a court case against the Oddfellows (IOOF) in Whitby, ON, by a would-be member who was injured by the initiation ceremony.14 MBiC preacher David S Shantz, leader of a tabernacle evangelistic campaign in Owen Sound, ON, attributed some of the limited response the team experienced to wickedness and secret societies in the town.15 Gospel Banner editor Henry Hallman disputed that the acts of the Masons were in fact true charity. He claimed their charity was given by contract and limited to one-time donations.16 At least one EMCC congregation in Ontario experienced limits to its growth for decades in the 20th century until finally a pastor managed to persuade adherents to set aside their lodge memberships.

When an MBiC field needed spaces for preaching, they did not feel compromised by renting halls owned by lodges, such as The Grange Hall on the 2nd line Nottawasaga, (which they eventually bought), or a hall used by Foresters, on Brunswick Avenue, Toronto. The Grange (“Patrons of Husbandry”) did not pretend to be ancient, like the Freemasons, but was a society invented after the American Civil War, meant to enhance agricultural workers’ lives. It involved re-enacting pagan mythology, used secret rituals and hand shakes and so on.17 A farm lobby group, the United Farmers of Ontario, had many Grange members in leadership and shocked everybody including themselves when elected enough candidates to form the Ontario government in 1919. One government minister was an MBiC preacher whom I will look at in later blogs.18 When the UFO government fell in 1923, they were replaced by the Conservative Party, which was dominated by Orange Lodge members.19

On the other hand, an Ontario-educated sometime member of the MBiC at Didsbury, Alberta, Joseph E Stauffer, was secretary for a fraternal order, the King Hiram Lodge (a Masonic group founded in Didsbury in 1906). I don’t now whether this ended his membership or not.20 Elected to the Alberta Legislature in 1909, he also enlisted in the Canadian forces, and died at Vimy Ridge, April 1917. Quite a journey for a Canadian Mennonite.

There was a time when applicants to membership in the MBiC or the UMC had to explicitly reject membership in oath-bound secret societies. In 1875 they “Resolved that no member of our Church be allowed to belong to any secret organization.”21 The 2013 “Articles of Practice” still charges that members “shall not hold memberships in oath-bound secret societies.”22 The whole idea of “membership” in a church is suffering from neglect these days, but that is another issue. The United Missionary Church of Africa, the large denomination founded by American and Canadian MBiC/ UMC missionaries in Nigeria, still requires an explicit renunciation of membership in secret societies, with good reason, because of the violent and evil work of such societies in the past and present in West Africa.23

Some good? I should acknowledge some anthropologists believe secret societies and cults provide community cohesion, cultural memory, and sometimes resistance to colonial oppression. Fine. This control however is frequently at the expense of others in their culture, as I learned from my Nigerian in-laws. Women and children have often experienced abuse from male secret societies, so I am not in favour of such groups just because they are “cultural.” All cultures and their institutions have harmful, God-rejecting aspects.24

Why would this be a problem in North America? As Wesley Gerig noted, aren’t associations merely a basic human behaviour?25 Humanly speaking, most people like to know secrets which others don’t and belong to inner circles of acceptance and power.26 Nothing exactly wrong with secrets. Christians do not live by “power,” however. North American 19th-century fraternal societies had worldly socially-approved purposes, for example, unity of the Empire (British) or country (USA), military solidarity, funeral insurance, channels for help and influence. The societies offered acceptance into society and political opportunities to selected minority individuals. The Freemasons were by no means the only such group, though best known. Someone estimated there were 800 such societies in the USA in the mid-twentieth century.27

Credit: Mary-Lou Patterson, “Open Secrets,” (ca 1983).

Mennonites rejected and were ostracized by the dominant Anglo culture, so in Canada the German-speaking groups were somewhat isolated from British Empire-boosting organizations such as the Scottish and English Freemasons, or the Anglo-Irish Orange Lodge. The Orange Order was particularly strong in Ontario and opposed Catholics, and occasionally tolerated rioting. Before the Temperance movement became strong, alcohol and male camaraderie was one of the attractions of Orange Lodge events.28 At one time Toronto’s Orange Lodge members dominated the city for political office, jobs and promotions.29 It is said every mayor of Toronto from 1850 to 1950 was a member of an Orange Lodge. Similarly, about half of the elected leadership of the small town of Harriston, ON, near Listowel and Palmerston, where the MBiC had churches, were Masons in one period.30 Many fraternal societies had a religious flavour as well, with odd theological views.31 None of these characteristics would encourage MBiC members to join. The Orange Order attracted less interest in Waterloo County’s German Lutheran and Mennonite areas, though they did organize.32 Elsewhere in Ontario they were able to capitalize on fears of non-British and Catholic immigration taking away jobs (nothing new) and eroding British culture.33 In Saskatchewan, the Orange Order, the Masons and the Ku Klux Klan, among others (nice company), successfully opposed a plan to resettle refugee Mennonites from the Soviet Union in 1930, describing them as aliens with foreign values.34 Orange Lodge membership has declined: eg Middlesex County is down to 5 lodges, Guelph has one still functioning.35

There were German Freemasons and similar groups in the period when European Mennonites were starting to migrate to Pennsylvania, but again European Mennonites were excluded from the networks of power and society, in addition their insulating doctrine rejecting secret societies and the use of oaths.36 As some Mennonites learned English and interacted with their host countries, some would feel the pressure to fit in even more in an atmosphere advertised as neutral to religion. This perhaps happened in the Didsbury area where Joseph Stauffer and a few others from the three Mennonite groups joined the societies.37

The Christian life is lived openly, “transparently,” as we say. In his trial, Jesus said he taught openly and not in secret (John 18:20). Later some teachers claimed Jesus did teach special doctrines to a favoured few (them!) in secret.38 Many times when former lodge members expose the secret oaths and rituals they went through, the lodges involved usually claim innocence and say, “Not true of our group.” When Peter warned of false teachers he said, “They will secretly introduce destructive heresies” (2 Peter 2:1c). His co-apostle Paul declared, “I have taught you publicly” (Acts 20:20).

Banner: Guelph Orange Lodge No.1331 interior. Credit: Anam Khan, Guelph Today, April 17 2021.

1E Morris Sider, The Brethren in Christ in Canada: Two Hundred Years of Tradition and Change (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1988) p 72.

2See EMCC History Blog, “Non-swearing of Oaths.”

3John C Wenger, Introduction to Theology: A Brief Introduction to the Doctrinal Content of Scripture Written in the Anabaptist-Mennonite Tradition 4th printing (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1975) p 225-226. MBiC Discipline (1924), under “General Rules for our Society,” Section XI: Secret Societies, p 36.

4 Anstead, Christopher J., “Fraternalism In Victorian Ontario: Secret Societies And Cultural Hegemony” (1992). Digitized Theses. 2118. Abstract. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/2118

5Wesley L Gerig, “The Lodge and the Lord,” in Missionary Church General Conference manual, 1985, p 116-120.

6William Kostlevy, “The Social Vision of the Holiness Movement,” in Kevin W Mannoia and Don Thorsen, ed, The Holiness Manifesto (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans, 2008) p 92-109.

7Eg Free Methodists: Benjamin T Roberts, Holiness Teachings (North Chili, NY: Earnest Christian Publishing House, 1893) p 17; Albert Sims, Bible Salvation and Popular Religion Contrasted 4th ed (Toronto: By the Author, 1888) ch 10 “Secret Societies,” p 61-72. Officially: Free Methodist Church of North America, The Book of Discipline 1985 Part 1 (Winona Lake, IN: Free Methodist Publishing House, 1986) p 27, 57. Nazarenes: Manual/ 1997-2001 Church of the Nazarene (Kansas City, MO: Nazarene Publishing House, 1997) p 45-46.

8John R Rice, Lodges Examined by the Bible (Chicago, IL: Sword of the Lord, nd) p 103 lists Dwight L Moody, Reuben A Torrey, also fundamentalists such as Paul Rader, and James M Gray.

9Neil Semple, The Lord’s Dominion: The History of Canadian Methodism (Montreal, QC and Kingston, ON: McGill-Queens University Press, 1996), p 58.

10Kostlevy, p 99.

11Leslie R Marston, From Age to Age A Living Witness: A Historical Interpretation of Free Methodism’s First Century (Winona Lake, IN: Light and Life Press, 1960) p 167-168.

12William H Brackney, “The Fruits of a Crusade: Wesleyan Opposition to Secret Societies,” Methodist History July 1979.

13 http://www.ubcanada.org/ub-church-history/

14Gospel Banner (November 15 1884) p 174 or a summary of “The Religion of Masonry” by a Rev J P Lytle from the United Presbyterian, in the Gospel Banner (1884) p 187.

15David S Shantz, “Report,” Gospel Banner (September 1891) p 5.

16Henry S Hallman, “Charity of Secret Societies,” Gospel Banner (1892) p 266.

17https://www.escarpmentmagazine.ca/community/the-secret-farm-philosophy/

18EMCC History blogs, “UFO Politician: Preacher Beniah Bowman” and “UFO Politician: The Honourable Beniah Bowman.”

19“Many Orangemen Elected June 25,” Winnipeg Free Press Evening Bulletin, (July 11 1923), listed 24 by name, including the premier-elect, Howard Ferguson.

20According to Aron Sawatzky, “The Mennonites of Alberta and their Assimilation,” MA thesis, University of Alberta (1964), p 51a-56, quoted in Frank H Epp, Mennonites in Canada 1786-1920: The History of a Separate People (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1974) p 326. Also, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial/detail/1576110

21Everek R Storms, History of the United Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1958) p 50.

22EMCC Articles of Faith and Practice, FP-2.8, subsection 2).

23The negative and sensational side as reported in Nigeria, see https://tribuneonlineng.com/nigerias-huge-market-of-blood-and-human-sacrifice/

24Patience Ahmed and others, edited by Lois K Fuller, Kingdoms at War: An Ethnic Survey of Niger, Kebbi States and FCT (Jos, Nigeria: CAPRO Research Office, 1995) p 208.

25Gerig, p 116.

26David V Barrett, A Brief History of Secret Societies (London: Constable and Robinson, 2007) p xi-xv. See also C S Lewis’ 1944 address on the lure of being in “The Inner Ring,” in C S Lewis, The Weight of Glory (Macmillan, 1980).

27Quoted by Rice, p 11.

28Lynne Marks, Revivals and Roller Rinks: Religion, Leisure and Identity in Late-Nineteenth-Century Small-Town Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996) p 110.

29 Jessica L Harland-Jacobs, Builders of Empire: Freemasonry and British Imperialism 1717-1927 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 2007). https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/orange-order

30Gregory Klages, “Freemasonic and Orange Order Membership in Rural Ontario during the Late 19th-century: A Micro-Study,” Ontario History (Volume 103, No 2 Fall 2011) p 192-214. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/onhistory/2011-v103-n2-onhistory04938/1065452ar.pdf

31Marks, p 114.

32Mary-Lou Patterson, “Open Secrets: Fifteen Masonic and Orange Lodge Gravemarkers in Waterloo and Wellington Counties, Ontario (1862-1983),” note 4, https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/mcr/article/view/17271/22720

33John English and Kenneth McLaughlin, Kitchener: An Illustrated History, 2nd ed. Toronto: Robin Brass, 1996) p 73-74.

34Frank H Epp, Mennonites in Canada 1920-1940: A People’s Struggle for Survival (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1982) p 314.

35https://www.guelphtoday.com/following-up/150-years-for-the-last-standing-orange-lodge-in-guelph-4226439

36 Niall Ferguson, The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook (New York: Penguin, 2018) p 49-53.

37Epp (1974), p 326.

38For example, The Secret Teachings of Jesus: Four Gnostic Gospels, translated by Marvin W Meyer (New York: Vintage Books, 1986).

Leave a comment