Practically all Christian traditions recognize the importance of holiness. For the EMCC, the Anabaptist/Mennonite, Pietist,1 and Wesleyan holiness traditions all encouraged their communities to turn away from enticements by the world. The Mennonites who were expelled from the Mennonite Conferences in the 1850s and 1870s (who became the Mennonite Brethren in Christ—the MBiC) accepted Methodist revivalist piety from, among others, the Evangelical Association. Before the merger that produced the EMCC in 1993, the Evangelical Association side also had become to a large extent holiness-oriented, so the same concern was there as well, though not always in the same terms.2

By the 1870s in North America, sanctification was widely promoted in a Wesleyan holiness form. This variety emphasized the Holy Spirit, holy love and holy living, victory over sin, being filled with the Spirit, baptism with the Holy Spirit, entire sanctification, and consecration. You name it, and the EMCC’s ancestors were interested in it.3 And so should we.4 Revivalist religion claimed to be real, earnest or radical Christianity. (“Conservative Christianity” language came later, under the influence of fundamentalism.) Yet non-conformity was nothing new to the MBiC.

Note: there is a non-Christian streak in western culture searching for a “simple life” which we could examine, but that would lead us astray from the current concern. This streak could be a clue to “the meaning of the universe,” or not.

Mennonite ethics. One section of the early EMCC (the Mennonite side) used an ethical category to guide some conduct which they termed “nonconformity.” Christians have long used a cluster of ideas and words suggesting similar concerns: separation from the world, from worldliness,5 and from the temptation to be respectable in the eyes of society. The presumed opposites were godliness or Christ-likeness. “Nonconformity” is a term rarely used today, for various reasons, some of which I may outline later. The phrase about separation from the world was on the masthead of the MBiC church paper the Gospel Banner for many years. Daniel Brenneman started it in the first issue: “Devoted to dissemination of Gospel Truth, Vital Godliness and Experimental and Practical Religion. Some of its leading features are: That Christians are a separate people from the World— ‘a peculiar people.’ That it is inconsistent with the Spirit of Christ which is in them to engage in Warfare….”6

In England, for centuries “Nonconformists” or “Dissenters” were those who did not submit to the established church, the Church of England (Anglican).7 More recently, American Mennonite historian C Henry Smith applied “Nonconformity” to those Anabaptists who did not “conform” to the state churches of Europe. They suffered for not submitting.8 In North America, Mennonites did not usually suffer physically for their faith. Probably many Mennonites who practiced nonconformity did not know of or bother themselves with the British usage. Mennonites seem to be the one church tradition that, in English at least, emphasized this word “nonconformity” for ethics.9 See the full and helpful article by Harold Bender (1958) and others (1990) on “Nonconformity” in the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online.10

Separation. Anabaptist concern to obey God rather than man began early in the movement. The Swiss Brethren’s Schleitheim Confession of 1527 enjoined separation from the world in the introduction and devoted the 4th Article to “Separation from the Abomination,” meaning the world system. Some examples of following the abomination were listed: “all popish and antipopish works and church services, meetings and church attendance, drinking houses, civic affairs, the commitments made in unbelief and other things of that kind….”11 Separation was in the minds of the Swiss Brethren in January 1525 when George Blaurock, Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz and friends baptized each other in obedience to their understanding of Scripture and contrary to the demands of the Zurich town council.12

Simplicity of life. The twentieth-century Mennonite theologian John C Wenger described nonconformity to the world and separation from the world, encompassed by the broader term “simplicity of life.”13 Mennonites have at various times and places chosen different practices to implement simplicity. An example in my library is Daniel Kauffman’s, The Conservative Viewpoint,14 with chapters dealing with Amusements and Dress. He mentions other concerns: secret orders, life insurance, mode of baptism, politics, commercialism, driving equipage and fancy houses.15 Kauffman used fundamentalist language in this book but was fully Mennonite in his desire for separation from popularity/ the world. His earlier book, Manual of Bible Doctrines, with its section, “Non-conformity to the World,” introducing other chapters on “Non-resistance,” “Swearing of Oaths,” “Going to Law,” and “Secret Societies,” and was written before “fundamentalism” was a movement.16 For Mennonites, clothing and buildings were to be simple and “plain.” In associations and business affairs, they were “pilgrims and strangers.” Mennonites, including the MBiC, for periods of time have been open to the charge of legalism and following human traditions above mercy.17 By legalism here, I do not mean “meriting salvation by obeying the law of God/ doing good deeds,” which Protestants regularly reject, and which Luther and others thought the Anabaptists had fallen back into. United Brethren writer Luke Fetters helpfully defines legalism for the holiness context: the belief “that certain behaviours are characteristic of a holy life…rules, usually unwritten, which are established in response to biblical interpretation and prevailing societal conditions.”18

Courtesy Missionary Church Historical Trust

Humility. The notion of humility in Mennonite theology is closely related to nonconformity, and paired with the opposite, pride. Theron Schlabach claims that in the 19th century Mennonite leaders in North America emphasized “humility,” always present as a biblical and devotional teaching, as an antidote to creeping cultural influences as well as religious ones from American revivalism and Pietism.19

The Brethren in Christ,20 an Anabaptist-related group which arose in Pennsylvania in the 18th century, and, theologically, one of the churches closest to the EMCC, also have a long history of consciously avoiding conformity to their world. Their members first entered Upper Canada about the time of the American War of Independence, and were in place in Niagara, Waterloo and York Counties as neighbours of Mennonites, reinforcing the non-conformity teaching. They judged questions in conference by the concept of “separation” from the world.21 Excellent reflections on nonconformity for contemporary Brethren in Christ are four essays in their historical journal, Brethren in Christ History and Life.22Many BiC were impressed by Wesleyan holiness in the later 19th century and in 1910 their General Conference accepted the doctrinal package, despite some opposition.

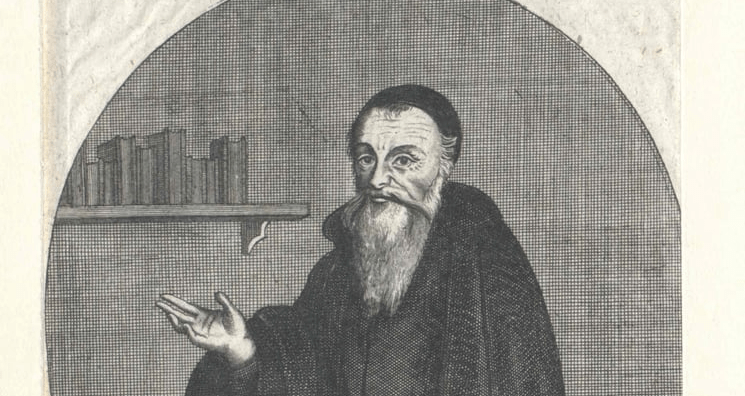

Banner: 17th century Dutch engraving of Menno Simons. Credit: Austrian National Library, Picryl, public domain

Since separation from the world’s ways was a concern of Wesleyan holiness churches, I will look at it in the next blog.

1See forthcoming EMCC History Blogs on Pietism as a dimension of the early and ongoing EMCC. On Pietist nonconformity, see especially ch 6 “World Negating or World Affirming: The Fallen World and the New World,” in Dale Brown, Understanding Pietism, rev ed (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Publishing, 1996) p 80-89.

2Hezekiah J Bowman, ed, Voices on Holiness from the Evangelical Association (Cleveland, OH: Publishing House of the Evangelical Association, 1882). UMCA Bible College Library, Magajiya, Nigeria, has a copy once owned by Jacob Hygema of the MBiC Indiana and Ohio Conference.

3Some of these terms are Keswick holiness favourites, but MBiC church ancestors were not always particular.

4The Keswick Conference streak in the Missionary Church added “deeper” or “Higher Life.”

5Eg Gerald Steele, “Just What is Worldliness?” Emphasis (October 1981) p 6.

6Gospel Banner (July 1878 Vol 1 No 1) p 1.

7This is the only sense noted in James D Douglas, “Nonconformity,” in Carl F H Henry, ed, Baker’s Dictionary of Christian Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1973) p 462. Douglas, a skillful Scottish editor of many fine dictionaries, may be excused for focusing on the main use of the phrase in Britain. But Henry’s editorial choices are clues that Reformed ethics has not been as interested in separation from the world as other traditions.

8 C Henry Smith and Cornelius Krahn, The Story of the Mennonites 3rd ed (Newton, KS: Mennonite Publications, 1950) p 46, 119, 123-124, etc.

9 Apparently in German no words quite correspond to the English term. The German Bible used words meaning worldliness.

10 Harold S Bender, Nanne van der Zijpp, John C Wenger, J Winfield Fretz and Cornelius J Dyck, “Nonconformity.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 3 Nov 2021. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Nonconformity&oldid=162933

11John Christian Wenger, Glimpses of Mennonite History and Doctrine (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1947) p 207, 209.

12Wenger, p 25.

13Wenger, p 113-114.

14Catalogued for example in Smith and Krahn in numerous places. See my forthcoming EMCC History Blog “Fundamentalism and the EMCC.”

15Daniel Kauffman, The Conservative Viewpoint (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1918) p 143.

16Daniel Kauffman, Manual of Bible Doctrines (Elkhart, IN: Mennonite Publishing, 1898) p 186-204.

17Several chapters in Virgil Vogt, ed, Radical Reformation Reader (Np: Concern Pamphlet Series 18, 1971) deal with this accusation, especially Walter Klaassen, “Radical Freedom: Anabaptism and Legalism,” p 138-146.

18Luke S Fetters, “The Holy Spirit in Sanctification,” in Paul R Fetters, ed, Theological Perspectives: Arminian-Wesleyan Reflections on Theology ([Huntington, IN: Church of the United Brethren in Christ], 1992), a resource I have found continually valuable.

19Theron F Schlabach, “Mennonites and Pietism in America, 1740-1880,” Mennonite Quarterly Review July 1983 (57:3) 222-240.

20Since 2017, the Canadian national church is called Be in Christ Church of Canada.

21E Morris Sider, Two Hundred Years of Tradition and Change: The Brethren in Christ in Canada (Nappanee, IN: The Canadian Conference, Brethren in Christ Church, 1988) p 71-82.

22Brethren in Christ History and Life (Vol 40 No 1) April 2017: 105-157, from a Conference on the theme: “Not Conformed: The Church, the World, and Christian Discipleship in the 21st Century,” at Messiah College, PA, in November 2016.

Leave a comment