The position and powers of ecclesiastical officials called (in English) “bishops” has gone through a lot of variation in history. The word in English is descended from the Greek word “episkopos” which meant foreman, overseer, one who watches over, or superintendent. It was a rather general word applied to a number of relationships. In the early Church, it was used of an activity which a number of people might do and stop doing when circumstances changed. It was not an “office.”

Change came however as the early Church spread. In some areas, the word “bishop” became a title for an office, even in the early second century. Ignatius bishop of Antioch (late first and early second century AD) thought of himself this way. Bishops fared differently in Ireland where monastic abbots had influence more like bishops elsewhere.1 Rather quickly the position gathered monarchical administrative powers in imitation of Roman imperial administrators in addition to a unifying and teaching function.2

From The Met, NY. Public domain

When the Reformation turned the western European Church’s attention freshly to the Scriptures, people compared the biblical precedent to the practices of the Church of the time, and numerous traditions were considered faulty. Some Lutherans were indifferent to the position of “bishop,” and would retain it or not; some supported a theory of apostolic succession. The Reformed Churches turned to a more functional structure of presbyters (elders), and Anglican attitudes varied from outright indifference to holding monarchical bishops to be essential, and others that it was “popish.”

The radical Reformers (Anabaptists, who led to Mennonites, Amish and Hutterites,) trying to be biblical, and using Luther’s German Bible, thought they needed to have a position of oversight called “bishop,” (German Bischof, Dutch oudeste [“elder”]) as well as preacher (German Prediger, or Deiner [“minister, servant”]) and deacon (Diakon.)3 The GAMEO articles describe how various Anabaptist groups adapted the institutions over time. These positions accompanied people to Pennsylvania and eventually to Upper Canada among the Mennonite settlers on the Niagara frontier, in York and Waterloo Counties.

What was a Mennonite bishop like in Ontario? Certainly not monarchial, with staff and palaces, a treasury, cathedral churches and the power to appoint ministers to this or that parish. They had no connection to territorial governments. The bishops did have authority over members in an area, but the meeting points were not congregations as we think of them now. Swiss-South German Mennonites in the 19th century in Ontario seem to have seen themselves as a fellowship geographically scattered by the settlement pattern, compactly in Waterloo, but much more thinly spread in York and Niagara. Even in Waterloo, Samuel J Steiner noted members in south Waterloo County were more spread out than in the northern township of Woolwich, and more susceptible to assimilation to Anglo-Canadian culture.4 Each area eventually had a bishop or bishops (Philippians 1:1), depending on the size of the region. The areas were somewhat informally related, though submission and humility were highly prized among Mennonites, and seniority mattered. They were unpaid. They often had to discuss community problems and settle disputes. In many cases, it could be a thankless job.

Frequently, bishops were selected by lot from suitable men in the Mennonite community. They stayed on their farms and exercised their calling by preaching alongside the other preacher-pastors, who often were selected in the same way. In some groups of Amish, each congregation had a bishop.

When New Mennonite followers were breaking out of the Canada Mennonite Conference in the 1850s, they accepted for a while the designation of “bishop” from John H Oberholtzer of Pennsylvania for some of their leaders such as Daniel Hoch (Niagara), John McNally (Waterloo) and Abraham Raymer (Markham—though this never seems to have been implemented in Raymer’s case).5 The positions faded from use for unknown reasons.

Solomon Eby (1834-1931) was selected by lot as the Mennonite preacher at Port Elgin at the same time his father Martin Eby was selected as a deacon (1858) soon after the congregation organized. Both these designations were ordained, more or less for life. The Port Elgin Mennonite Church acknowledged the leadership of Waterloo County bishops.

Methodist structures. I can’t emphasize this enough. During the formation of the Mennonite Brethren in Christ Church (1874-1883), the church adopted the structure (set out in its document The Doctrines and Discipline) of the Evangelical Association (Evangelische Gemeinshaft), itself modeled on the Methodist Episcopal Church in the USA. John Wesley had appointed two “superintendents” for the societies in the American colonies and he was unhappy that American Methodists, freed from British legalities by the War of Independence, chose to rename their leaders “bishops.” The Evangelical Association (EvA) imitated this structure. Its bishops did not seem to have territories. The EvA did not have a bishop living in Canada—membership was too small in relation to the US Conferences. One of the US bishops would come and chair the Canada Conference Annual Conferences, such as John Jacob Esher from Chicago. At the Lingelbach Church in 1899 he urged the Canada Conference to take up missionary work in the Canadian North West Territories. The Conference responded, sending William Beese and his new wife Barbara to Winnipeg as a start.6 Within 28 years the EvA had a new Northwest Conference organized with 1433 members in 21 circuits.

No bishops. The authority of Evangelical bishops became a matter of contention in the 1880s and led to a split in the denomination, not healed until 1922. Perhaps this was one reason for the MBiC to hesitate about introducing bishops, even though closely allied groups such as the Free Methodists on the Wesleyan side and Brethren in Christ on the Anabaptist side, had them.7 The MBiC did not, after all, adopt the level or position of bishop, but stopped at “Presiding Elder” as an annually elected leader in the Conferences. The role of James the brother of Jesus “presiding” at the Jerusalem conference (Acts 15:13) probably suggested the term to Methodists. Conferences could have more than one Presiding Elder if numbers or convenience required it. Ontario often had two. As an experiment, for two years they even tried having four. The binational MBiC Conferences also worked together through an Executive Committee, led by a chairman. Their work had to be ratified by the General Conference.

One reason sometimes given why the MBiC did not continue the position of bishop is that its leaders had had conflicts with Mennonite bishops and therefore wanted more autonomy for the pastors. One sign of this is that from the start, MBiC pastors could baptize converts without the presence of the Presiding Elders, whereas under the Mennonite Conference, candidates for baptism were presented to the bishop or bishops to approve and baptize. This was one of the complaints against Solomon Eby; he had not waited for a bishop from Waterloo to come to Port Elgin (Bruce County) for his candidates to be baptized.

Yet under the Discipline adopted by the MBiC, the authority of a Presiding Elder was more widespread geographically than Mennonite bishops, and a Presiding Elder’s presence was needed every three months to conduct the Quarterly Conferences and ordinances of a field (=circuit), that is, the Washing of the Saints’ Feet and the Lord’s Supper. Every officer in the field had to be “passed” by vote by the members of their class every quarter. Reading Quarterly minutes suggests to me there was quite a bit of forgiveness in the system for ineffective officers (pastors, stewards, class leaders, deacons, Sunday School superintendents, et al) nevertheless, the Presiding Elder had considerable close oversight of most of the congregational positions in his district. Everek Storms said of Milton Bricker, one of these Elders, “A friend to everybody, he knew personally practically every member and adherent in the Ontario District from the oldest grandfather to the youngest child.” (History of the United Missionary Church, p 90) They had the authority to station preachers to fields needing them due to sudden changes in personnel, and to suspend preachers for breaking significant rules of the Church (discipline and doctrine). A Presiding Elder chaired the Annual Conferences. EMCC historian Eileen Lageer agreed that in the MBiC, Presiding Elders could be fairly autocratic.8 A Mennonite historian judged the power of an MBiC Presiding Elder was greater than a Mennonite bishop ever had.9

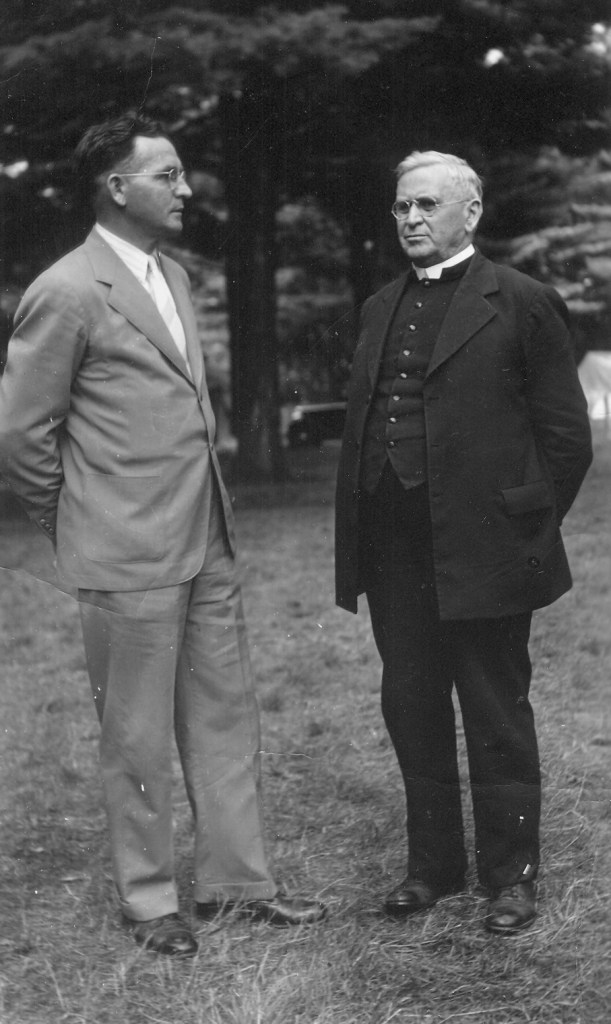

Courtesy Missionary Church Historical Trust

Pastoral appointments. One traditional power of bishops in various denominations has often been the assignment of pastors to parishes or congregations. This power led to frequent clashes in Methodist churches in the USA and several schisms. Although in the first years, the MBiC assigned ministers by a committee made of senior preachers, amazingly, soon they came up with a “stationing committee” structure that consisted of the Presiding Elder and sometimes a recently retired Presiding Elder, but also all the delegates of the fields, that is, non-preachers, as many as 20 of them, if I understand the system. I hesitate to call them lay people because I don’t like the “clergy-laity” division as a non-biblical distinction, still, full-time and non-full-time ministers (Ephesians 4:11-12 calls all believers ministering people), is a significant difference of life-experience. This structure lasted until 1955.10 So the Presiding Elders, though given wide authority, and the “clergy,” did not necessarily control the stationing process, under the MBiC/ United Missionary Church.

Request to discuss the position. Concerning the lack of bishops, the Canada Conference (after 1907 called the Ontario Conference), several times sent to the MBiC General Conference petitions for the denomination to establish or at least discuss the position of “bishop.” The petitions were never successful, but the issue was debated. I do not know what kind of bishop the petitioners wanted, nor can I identify from whom or from which section of the Conference this persistent request came. I haven’t seen other Conferences ask for this. It may have been as before, simply the fact that the Bible in the Authorized Version (KJV) used the word in its translation: they wanted to be scriptural in terminology, a valid concern. It could be that the MBiC, being a coalition of Conferences with various origins,11 was not operating at an optimum level of unity to satisfy some. The highest body in the denomination, the General Conference, met every 4 years, and a few pieces of necessary business were delegated to the Executive Committee between Conferences. This led to slow changes in the Discipline, and minimal coordination Conference to Conference, whether it was publishing the Gospel Banner, choosing textbooks in the Reading Course, revising doctrinal statements, responding to cultural change, missionary action or hymnbook production. Maybe some thought the office of a bishop or bishops could get the denomination going. I suspect Sam Goudie was one of those people, but I cannot prove it. He was definitely in favour of a centralized mission society, and was President of it (the United Missionary Society) from 1922 to 1938, and a member/ leader of the denominational executive 1912 until 1943.

When the large and wealthy Pennsylvania Conference declined to adopt a new name and new Discipline in 1947/1952, and dropped out of the denomination, the way seemed clear for those desiring a centralized church. You can sense this relief in Storms’ 1958 history of the Church.12 This allowed the denomination to prepare for a merger with the Missionary Church Association (MCA) by adopting a Constitution, under a General Superintendent (still not called a bishop!), similar to the MCA. After the merger (1969) that position became a “President,” representing quite another model of leadership.13 The Missionary Church of Canada also adopted a position called a president (1988), at first part-time and volunteer, but eventually the EMCC increased the functions and powers of the presidency into a full-time paid position, answerable to a National Board.

Postscript. The stationing committee was replaced by a conference or district-elected “pastoral relations” committee still involving the district superintendent and a congregation’s board in 1955. The 1969 merger with the Missionary Church Association introduced the MCA “congregational call” system to the whole North American Missionary Church, with still more initiative expected from a congregation. After the 1993 merger of the Evangelical Church in Canada and the Missionary Church of Canada, the districts still controlled the credentialing of ministers, but the call system was extended to the whole EMCC because the ECC had operated with a superintendent-led system of appointment.14 In my opinion, the culture-conforming congregationalist/ Baptist system continues powerfully into the 21st century. The EMCC abolished districts (and hence District Superintendents) in 2005. Because I was outside Canada teaching in Nigeria I missed the discussions and returned on home assignment in 2006 surprised to find it all over and done.

The national Church still controls credentialing of ministers, but often after the fact of a call being extended. The EMCC put in place a structure of several Regional Ministers (RMs) across the country with advisory roles and involvement in inducting and ordination ceremonies for pastors and congregations. Congregations still run into problems and may turn to their RM for help. I have asked leaders if they felt any pressure to increase the responsibilities of the RMs to more closely resemble the former superintendents’ authority, and received ambiguous replies. I am interested to see how the future unfolds.

Banner: A king investing a bishop with staff of office. AD 1000-1500. Wikimedia Commons. public domain

1Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity (New York: Harper & Row, 1953) p 332; Eric John, “The Social and Political Problems of the Early English Church,” in Anglo-Saxon History: Basic Readings, ed. David A E Pelteret (New York: Garland Publishing, 2000) p 34. Other areas of the Roman Empire did not have bishops ruling as Ignatius assumed he should.

2Reflected in the assumptions of the much-touted World Council of Churches Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document of 1982.

3Check the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO) for histories of the positions, eg https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Bishop ; https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Deacon

4Samuel J Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands: A Religious History of Mennonites in Ontario (Kitchener, ON/ Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2015) p 117.

5“1st Annual Conference of the united division of the Mennonite Church in Canada West and Ohio, assembled May 25 1855 at the Carlisle [ie Blair, ON,] school and meetinghouse, Waterloo Co., C. W. [Canada West],” in the MBiC collection, Mennonite Archives of Ontario, Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, ON. John McNally of Waterloo was added as a bishop in 1858.

6Eileen Lageer, Common Bonds: Story of the Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada (Calgary, AB: Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada, 2004) p 54-56. Within 9 years, the EvA had sent four more preachers and a Presiding Elder, Louis H Wagner, one of the men Sam Goudie heard in Toronto in 1903, when he hoped to hear the EvA Bishop Sylvanus C Breyfogel, as mentioned in the blog “The EUB Connection Part 2: after 1968.”

7In recent years the Be in Christ Church of Canada has dropped the term “bishop” in favour of a non-credentialed Board of Directors which hires an Executive Director, yet another culture-reflecting governance model. I should acknowledge that John Wesley’s “society” model was also a popular cultural structure of his time. Some Mennonite Churches have also dropped the position of bishop as well.

8Eileen Lageer, Merging Steams: Story of the Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1979) p 124.

9Frank H Epp, Mennonites in Canada 1789-1920: The History of a Separate People, (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1974), p 153.

10Everek Richard Storms, History of the United Missionary Church (Elkhart, IN: Bethel Publishing, 1958) p 220.

11See EMCC History homepage “Formation of the EMCC” for some of the stages and names.

12Storms, p 76-81.

13Although “President” is etymologically related to the older “Presiding Elder” term, in practice, the idea of a directing executive leader, who hires and fires staff, tinged with American republican practice, shifted the expectation of the term irrevocably elsewhere. This centralizing also allowed for a forceful shift to a clearly Wesleyan holiness doctrinal alignment favoured by the first General Superintendent Kenneth Geiger in the remaining Conferences, and away from Anabaptist doctrines of non-resistance and Washing of the Saints’ Feet, for example.

14Lageer, p 208.

Leave a comment